Hey there, stranger! Welcome to my Substack. If you sign up to receive it in your email inbox, I’ll send you e-copies of both my published books for free. You can scroll to the bottom of this post for more info, or else just enter your email address here:

Oscar nominations just got announced! There were surprises! And some predictable stuff! And . . . other stuff?

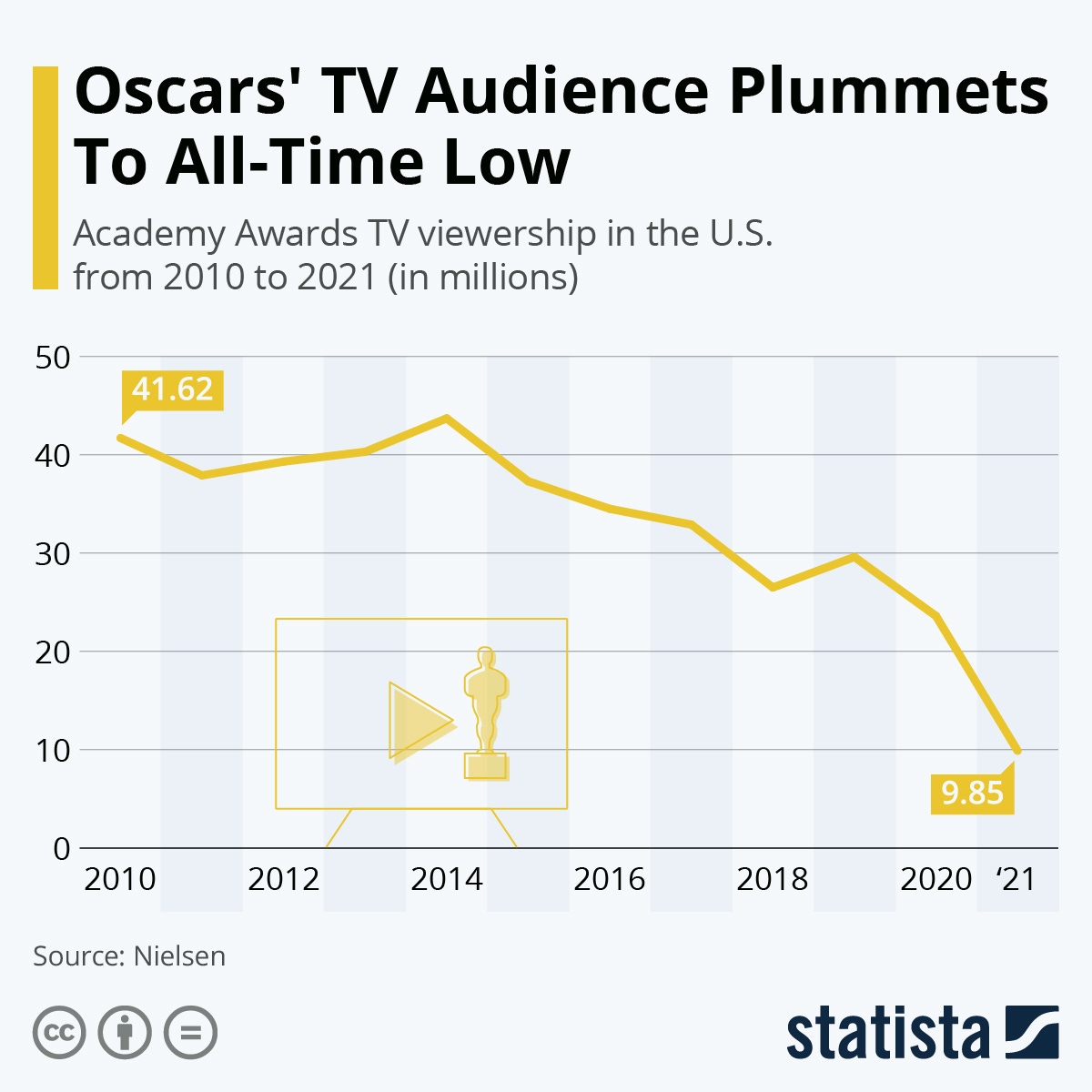

K, I’mma be honest, I didn’t really look at the nominations that closely because I just . . . don’t . . . care. And, according to a very popular headline, I’m far from the minority there. At this point, it’s become a bit of a cliché to point out that no one cares about the Oscars—but it isn’t wrong. The TV viewership of the Oscars has been in a freefall for at least a decade, as this chart helpfully shows:

So what gives? Has the public just become a mob of knuckle-dragging morons who only care about movies that feature capes and explosions? I mean, yes, but I think there’s a structural problem much deeper than that. It’ll take me a second to explain it though, so bear with me here:

First, we need to talk about the difference between an Oscar and an Emmy.

Let’s start here: In the U.S.—for some reason—there are four entertainment awards that are seen as the major entertainment awards. The Emmy (television), the Grammy (recording), the Oscar (film), and the Tony (live theater). This is where we get the acronym EGOT—an elite club of (so far) only sixteen people who have won all four (including Richard Rodgers, Whoopi Goldberg, and Mel Brooks).

Now why is it those four? Why not the Golden Globes or the MTV Video Music Awards—or, for that matter, the Pulitzers or the Game Awards? (You’re gonna tell me that video games are niche entertainment but Broadway musicals aren’t?) I don’t know, but the differences in how those four awards approach things tells you . . . a lot about the entertainment industry.

In short, while there’s not much difference between television and film as art forms—which I’ll get to in a second—there’s a huge difference between how the Emmys and the Oscars operate: Every year the Emmys give out hundreds of awards while the Oscars only give out a couple dozen. The Emmys give out awards for multiple genres, multiple time slots, and even have special ceremonies for children’s entertainment, technical categories, and regional programming.

In other words, the Emmys are designed to celebrate as much of the television industry as possible every year, but the Oscars are almost the exact opposite: they’re designed—deliberately or otherwise—to demarcate what is and isn’t “legitimate” cinema; there can only be one “Best Picture” at the Oscars.

Now, there are advantages to that: it makes the Oscars seem more prestigious, and it makes Oscar night more suspenseful and dramatic. But there are disadvantages as well: it makes Oscar voters feel like they have to honor something Important (i.e., World War II and/or Meryl Streep), and aspiring “prestige” filmmakers feel a lot more pressure to reverse-engineer previous award winners in order to improve their chances (e.g., “Better put Meryl Streep in this World War II pic!”).

Let’s state the obvious: Film and TV are not actually different things.

It’s kind of weird how rarely this is acknowledged, but . . . film and TV are pretty much the same thing, at least on the consumer end. They’re moving pictures synced to sound, in order to entertain and inform. Obviously, there are historical and technical differences—but digital technology and Reagan-era deregulation have rendered these differences mostly moot.

Most second-tier awards, like the Golden Globes and the SAG Awards, actually acknowledge this, giving out awards for both film and television. The reason that the “major” awards are separate is a long and complicated one, but it’s mostly a relic of the early days of TV when the film industry regarded TV as direct competition and the then-monopoly-hating federal government was working overtime to keep them out of it, anyway.

The gulf between the two industries, though, has led to some pretty specific eligibility requirements for winning an Oscar—for instance, if you want your film to be Oscar-eligible, God help you if you show it on TV. It probably goes without saying that this makes it sort of a big ask for viewers to see nominated films, and not just during a pandemic. (An awful lot of films get released on a bare minimum of screens to qualify—either because producers don’t have the budget for more, or because they’re counting on awards and nominations to help with the marketing push on their wide release, or both.) And while Emmy has shown a pattern of embracing new distribution channels like cable and streaming (see previous point!), Oscar has repeatedly put up a wall with a big sign that says “No! Theatrical stuff only!”

And that’s not an argument that Oscars and Emmys should merge (there’s no way they’ll be doing that, and I don’t personally care, anyway); it’s just setting me up for my next point:

Viewer tastes actually haven’t changed as much as you think.

I read an article a few years ago—can’t find it at the moment, sorry—whose gist was, “It’s not the Oscars’ tastes that have changed, it’s the public’s.” In other words: “Yeah, the Oscars mostly just honor stodgy period dramas, but that’s what they’ve always honored. It’s the public who’ve decided that they want nothing but capes and explosions.”

“The Oscars cannot fail; the Oscars can only be failed.” Or something.

Even that sort of obscures what’s going on, though. While the box office has been dominated by “capeshit” for the last couple of decades, in that same era, so-called “prestige TV” has been a massive success. I could name shows all day here, but you know what I’m talking about: The Wire. House of Cards. Breaking Bad. Game of Thrones. Etc., etc., etc. There’s still a market for Very Serious Drama; it’s just that the public is staying home to watch it.

Why? Because—as we’ve said—TV and film are not actually meaningfully different things. The advantages that film had over TV—better picture, relative lack of censorship, the ability to choose what you watch—have evaporated in the last twenty years. The only meaningful difference left is that the cinema screen is bigger, and consumer behavior is going to reflect that. Explosions may be a lot cooler on the big screen, but emotions are just as powerful, regardless of whether or not the single tear rolling down Meryl Streep’s cheek is the size of a house. So it’s not so much that the public doesn’t care about Very Serious Drama; it’s just that there’s no strong argument for leaving your house and spending fifty bucks to experience it. The proposed “Best Popular Picture” Oscar is condescending, yes, but it’s especially condescending when you consider what the existence of “prestige TV” implies: most Oscar nominees absolutely would be popular, if they were a bit less inconvenient to watch.

We can get as precious as we want about what constitutes “real” cinema, but the average consumer is going to prefer to consume entertainment in the way that’s most convenient and enjoyable for them. Which brings me to my next point . . .

Why are we still being so precious about what a “movie” is?

It’s hard to think of another form of entertainment where creators get as pretentious about it as they do the movies. Analogies to other art forms are so bizarre that they’re almost painfully stupid to type: Imagine Stephen King saying, “You haven’t really read my books unless you’ve purchased the hardbacks.” Or Shigeru Miyamoto announcing that you’d only really played his games if you’d played them at the arcade.

Again, it’s almost too stupid to imagine, but for some reason it’s a not-at-all-rare, totally-normal thing for film directors to talk about their movies that way. Here’s Martin Scorsese being sad that almost no one would see The Irishman on the big screen, and David Lynch railing against people who watch movies on their phones, and Christopher Nolan losing his mind at Warner Bros.’ decision to let people watch their movies at home during a pandemic.

Now—I’m not saying those guys are entirely wrong! There’s a solid argument to be made that the movie theater is the ideal way to watch a movie. One of my undergrad degrees is in film studies, so I’ve got as much wistful nostalgia for the silver screen and the clickety-clacking projector as anyone. But there are a couple of things that need to be said here.

First of all, when Martin Scorsese waxes poetic about the theatrical viewing experience, he’s thinking of the lavish theaters on Hollywood Boulevard, not the miserable, sticky-floored, crying-baby-filled, operated-by-teenagers-who-don’t-have-a-clue-about-how-to-project-a-movie multiplexes most of us have to go to. More importantly, though, this whole attitude just strikes me as a really unhealthy way to think about your art form. If you want the masses to care about your art, you need to meet them where they are.

As a writer, I would greatly prefer that people read my books under ideal conditions—comfortable chair, mood lighting, relaxing beverage, hours of free time so they can give rapt attention to my every word—but I know a lot of them are going to skim them on a plane, sitting next to some shoeless drunk guy with a foot fungus. That’s just reality. And all things considered, I’d rather have distracted readers than no readers.

I know some artists may disagree! If you want, you can choose to be like Christopher Nolan and get mad that people are going to watch your movie on a TV so they can turn on closed captions and actually decipher what your characters are saying—but you don’t get to be elitist about your art form and then wonder why the average person has lost interest.

“Okay,” you’re saying, “what’s the solution, then, Mr. Film Expert Guy???”

I mean. I don’t really have a solution. As much as I love cinema, I find the whole awards-show cycle eye-rollingly tiresome, and I’d be happy if it just went away.

Realistically, though, that’s not going to happen. If you’re trying to sell your film on actual quality, a opposed to explosions or gratuitous nudity, you sort of have to chase after awards. As I’ve said elsewhere, I’m not above that sort of thing—awards, like nudity and scandal, are a great way to attract attention to your work.

Fundamentally, though, you can’t be simultaneously elitist and populist. You don’t get to fuss endessly over the exact right and proper way to experience your art and then wonder why no one is bothering to experience your art. If you think your movies are valuable—and not just valuable to wealthy art obsessives on the coasts, but valuable to actual people—you have to put them where people will actually see them.

It’s not popular to say it, but I think the real solution here is to embrace streaming. Back in the before times, AMC Theaters used to do a thing where they would marathon all the Best Picture nominees in a day or two; that’s not really feasible now, but how cool would be if there was an easy way to just mainline them at home without subscribing to a dozen different services? One lump sum to watch them all on Prime Video, or whatever?

I don’t know. If you’re fixated on the theater as the Only Correct Way to Watch Movies—and in the midst of a pandemic, you really shouldn’t be, but—you’re going to have to give viewers a compelling reason to come out and see your movies there. Maybe slash ticket and concession prices? Or at least get some popcorn that isn’t stale?

Haha, just kidding. We all know “munching extremely stale popcorn” is the only Martin Scorsese–approved way to watch a movie.

Reminder: Subscribe to read both my books for free

Welcome to any new readers! I’m a horror writer and/or humorist out in Madison, Wisconsin. I’m working on building my audience, so if you sign up to receive this newsletter in your email inbox every month, I’ll thank you with free e-copies of both my books. So that’s:

Ophelia, Alive: A Ghost Story, my debut novel about ghosts, zombies, Hamlet, and higher-ed angst;

Murder-Bears, Moonshine, and Mayhem: Strange Stories from the Bible to Leave You Amused, Bemused, and (Hopefully) Informed, an irreverent tour of the weirdest bits of the Christian Scriptures;

plus my monthly thoughts on horror novels, musicals, and the publishing industry; all for the low, low price of . . . nothing. It’s free. Why? Because I like you.

Click here for a bit more info about me, or enter your email address below to start reading both books right away:

Stuff I’ve been enjoying lately

I was never really a Christian journalist, but the internet sure seems to think I am. I get press-release emails constantly about the latest Christian music, film, etc.; I’m so used to it, I don’t think about it anymore—I delete them or skip over them, whatever.

Recently, though, one Catholic hip-hop artist—a guy who goes by “Mandala”—decided to be really persistent. When I ignored his first email, he sent me another. After a couple, I was like, “Ugh, fine, I’ve never heard ‘Catholic rap’ before, I guess I could give it a try.” So I listened to the single he linked to, and . . . wait, this was really good. Not just a sick beat and some dope rhymes, but some real humility, conviction, and theological insight. How was this a thing?

So I invited him on my podcast—episode will probably go live in April—and I checked out his debut album, American Pope. Guys, every song on this thing slaps. My personal highlights are probably the dixieland piano of “Dala Man” and the smooth R&B of “You Should Be Dancin’,” but there really isn’t a bad track on this thing.

Give it a listen. You won’t be disappointed. Hope this kid goes far.