I just read My Best Friend’s Exorcism and I have questions

A spoopy Halloween special for my Substack besties

UPDATE 12/30/21: I’ve decided to make both my books (Ophelia, Alive and Murder-Bears, Moonshine, and Mayhem) permanently available for free to everyone who signs up for my Substack. Click the link below to start reading both immediately:

SPOILERS FOLLOW for My Best Friend’s Exorcism and The Exorcist.

* * *

As a rule, I tend to have a strong knee-jerk reaction against pop culture nostalgia, and I’m still not quite sure why. It may go back to the fiction-writing course I took my freshman year of college, when our instructor told us not to set our stories in a time other than our own unless there was a clear reason for it (and for some reason that stuck in my head as a sacrosanct rule, instead of just a bit of probably-good advice). It’s also possible that nostalgia has just been tainted for me by Boomer memes like this one:

There’s just something vacuous about congratulating yourself for existing simultaneously with pop culture that (surprise!) you enjoyed. Like, congrats on being entertained by entertainment, I guess, but your only contribution to it was consuming it. If that’s where you get your sense of identity … welcome to late-stage capitalism?

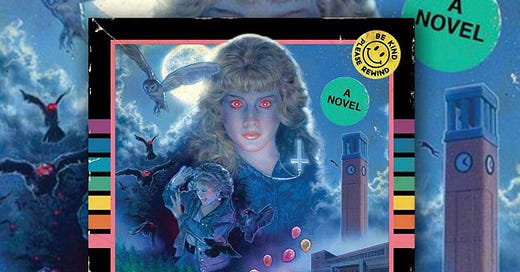

Whatever the reason, though, that cynicism was gnawing at me the whole time I was reading Grady Hendrix’s 2016 horror-comedy novel My Best Friend’s Exorcism — a book so awash in nostalgia that every chapter is named after a hit pop song from the eighties. It was a book I enjoyed more than not, and I don’t regret reading it, but it was also a house of cards built on pop culture nostalgia, so, unfortunately, I’m going to have to tear it apart, anyway.

* * *

Any serious discussion of exorcism horror has to start with a discussion of William Peter Blatty’s 1971 novel The Exorcist, mainly because every exorcism story of the last fifty years has been a ripoff of it. When Blatty published the book, though, he wasn’t looking to launch a subgenre — as a devout Catholic, Blatty’s primary goal was to bring awareness to the phenomenon of demon possession, which he regarded as evidence for the truth of the Catholic faith. Blatty actually based the book on a real exorcism that took place mainly in St. Louis in the 1940s, and his original idea had been to write a nonfiction account of it — or possibly even persuade Fr. William Bowdern, the priest who performed it, to write the book himself (Bowdern obviously wasn’t into the idea).

True story or not, though, writing it as a novel required Blatty to follow certain storytelling conventions, including a big climax at the end. I can’t track down a source at the moment, but I remember once hearing a real-life exorcist say that genuine exorcisms are often mainly about boring the demon out of its mind until it goes away, which obviously doesn’t lend itself well to the structure of a novel. So Blatty went for a big third-act twist instead.

*(Once again, SPOILERS FOLLOW for anyone who hasn’t read this fifty-year-old book, or seen the almost-as-old movie)*

At the climax of The Exorcist, the demon Pazuzu has managed to kill Father Merrin, the priest sent to exorcize him. Merrin’s protégé, Father Karras, angry and desperate, challenges the demon to leave the young girl it’s inhabiting and enter him instead; having taken on the demon, he jumps out the window, killing himself but banishing the demon in the process.

It’s an ending you can pick apart if you want (wait, how does Karras’s death prevent the demon from re-possessing the girl?), but it provides the fireworks for the climax while also making Blatty’s theological point: Karras, like Christ, takes on the evil infecting the girl and gives his life for her. You probably need a basic understanding of Christianity to catch the allegory, but it works for what it is.

I mean, as we’ve said, The Exorcist launched an entire subgenre, so clearly it did something right.

* * *

If Blatty’s intent with The Exorcist was to turn readers into Catholics, the novel was arguably a failure, at least in the long term; as with all genre-launching works, the thoroughly serious Exorcist simply gave way to less-serious ripoffs, and eventually out-and-out parodies. (Only seventeen years passed between the launch of the movie version of The Exorcist and the release of Repossessed, a spoof in which Exorcist star Linda Blair shared billing with Leslie “Don’t Call Me Shirley” Nielsen.)

My Best Friend’s Exorcism — which, with fewer jokes than you might expect, given the title, is a bit more pastiche than straight parody — follows the structure Blatty established with The Exorcist pretty closely. It begins with a slow build, taking its time to craft the titular friendship, before launching into a possession-inciting incident, a voyeuristic account of demonic horrors, a failed exorcism attempt, and — again, like Blatty’s novel — a third-act twist that dispels the demon once and for all.

The main joke of My Best Friend’s Exorcism, though, is that it takes place in the eighties. (Get it? The eighties! That’s … the whole joke.) It’s an unabashed nostalgia piece in which the friendship between the two central characters, Abby and the eventually-possessed Gretchen, is built on stuff like E.T. and Madonna, and when the exorcist shows up, he’s not a Catholic priest but instead is a member of a spoof version of The Power Team. (Remember The Power Team? They were a bunch of steroid-addled muscleheads who would visit schools and churches to tear up phonebooks and tell kids to stay off drugs and/or follow Jesus. It was … the eighties. Haha, the eighties!)

*(Once again, the next few paragraphs contain SPOILERS for anyone who hasn’t read this book, which is probably quite a few of you, you bunch of illiterates)*

As in The Exorcist, the initial exorcism attempt in MBFE fails, though Hendrix is merciful enough to let his muscleheaded preacher live — he runs away like a coward instead. When Abby realizes he’s not coming back, she attempts to exorcize Gretchen herself. The standard religious rite isn’t working, though, so she turns to — yep — eighties pop culture:

“By the power of Phil Collins, I rebuke you!” she said. “By the power of Phil Collins, who knows that you are coming back to me against all odds, in his name I command you to leave this servant of Genesis alone.”

The incantation goes on for quite a while, and mentions everyone from E.T. to Madonna to Geraldine Ferraro, but you get the idea. And yes, it works. The demon is cast out.

And when I read this part — possibly for the reasons I outlined at the beginning of this piece — I wanted to throw my book across the room.

* * *

It might have been because I read MBFE back-to-back with The Cult of Smart, a (really excellent) treatise on education by Purdue professor and avowed Marxist Freddie deBoer, but I had trouble reading the climactic scene without thinking about the Marxian account of religion. “Religion,” Karl Marx famously wrote, “is the opiate of the people.” It’s a line that’s been quoted out of context a thousand times, but the gist of what Marx was getting at was that religion’s primary appeal to the disenfranchised was as a coping mechanism. In Marx’s purely materialist account of reality, there is no hope for the miserable masses outside of political revolution; religion functions at best as a metaphor for material struggle and at worst as a distraction from it.

Now, if Marx was correct about his materialist conception of reality, and there are no gods, angels, or demons, then yes, religion is just cope. Barring utopian revolution (and even afterwards, if we’re being honest), all of life is essentially just hospice care: We’re all on our way to the grave, so we might as well make ourselves comfortable in the meantime. And in that sense, one “opiate” is as good as another. If religion makes you feel better and gives you a sense of purpose and identity, that’s great; if not, try something else. If Marx was right, then pop culture is a perfectly good substitute for whatever deity you can name.

However — and I can’t stress this enough — if freaking demons exist, then, um, Marx wasn’t right.

* * *

I’m far from the first person to point this out, but religion-themed horror — at least when it’s written by the nonreligious — nearly always has a certain schizophrenia to it: “Christians are a bunch of misguided, hypocritical bigots,” these stories tell us, “but also they’re basically correct about everything.” So, for instance, if you’re writing witch-themed horror set in New England, you have to mock those puritanical Puritans for superstitiously (and puritanically) hunting and killing witches — but also, you have to concede that witches are, in fact, real and dangerous, or else the story won’t work. But of course, because you can’t decide whether the Puritans were right or wrong to fear witches, the story ends up not working, anyway.

I suspect that a lot of these problems stem from authors being influenced by seminal works in the genre without really understanding them. Nathaniel Hawthorne’s “Young Goodman Brown” — probably the quintessential creepy tale of bad witches and worse Puritans — works because it uses witchcraft as a metaphor for the Calvinist understanding of human depravity, making it clear that the distinction between a Puritan and a witch is, in a Calvinist framework, a nonexistent one. Similarly, Blatty’s The Exorcist sells its third-act twist by understanding a Catholic theory of atonement — that there is no redemption without blood sacrifice.

With My Best Friend’s Exorcism, though, Hendrix falls into the trap of writing about religion without particularly understanding it. His Christian characters appear to be broadly Pentecostal — but they’re the sort of Pentecostals who own mansions and found expensive private schools, which definitely wasn’t a thing in the eighties. All of them are vocally anti-Catholic — but the chaplain at their presumably-Protestant parochial school is inexplicably referred to as “Father Morgan” throughout the book (and yes, there’s a gay joke at his expense). When it’s implied that the Satanic Panic was about something real (and, in fact, it’s apparently a Satanic rape that triggers Gretchen’s condition), you’d expect these Pentecostal-ish Christians to readily believe it, but … nope.

Fundamentally, though, my issues with MBFE are less about a failure to understand religion and more about a failure to understand why genre tropes work. MBFE, particularly at its climax, is an exercise in taking the formula established by The Exorcist and playing Mad Libs with it. You need a big, third-act twist, so … why not swap Jesus out for Phil Collins?

But … here’s the thing. If demons are real — and in the MBFE universe, they clearly are — it’s not hard to imagine them being afraid of Jesus (assuming, of course, that Jesus is also real in this universe). The God of the universe, who conquered death? Sure, he sounds like a guy whose bad side you’d want to avoid.

What I can’t imagine, though, is demons being scared of a balding prog rock drummer who thinks the word “Sussudio” means something.

* * *

Someone’s going to tell me I’m taking this too seriously and/or missing the point. The pop culture climax is just a gag, the final punchline in the “Haha, it’s the eighties!” joke Hendrix has been telling throughout the book. And it’s not really about the pop culture — it’s all just synecdoche for the friendship that Abby and Gretchen have been building over the years.

And those people are right. Like, I get it. The demon is cast out not by Phil Collins per se, but by the power of bein’ besties. But … again, what demon outside of the My Little Pony universe is scared of friendship? Especially friendship built on something as flimsy and ephemeral as enjoyment of “Material Girl”?

If I’m being honest, it’s that ephemerality that really got under my skin. While the world’s largest religions — for good or for ill — have survived for countless generations, it’s hard to imagine anyone under the age of thirty getting much of anything out of MBFE, because pop culture’s shelf life tends to be so short. What the heck is a Phil Collins? Nobody in their teens or twenties knows — he’s been cast on the Heap of Stuff only Boomers and GenXers Remember — and most people who remember the stuff in that heap probably aren’t even sure why they remember any of it, aside from their grasping for something (anything!) to cling to as identity in an alienating world where demons lurk everywhere and God is dead.

Or … something.

And, if I’m honest, The Exorcist is probably sitting there, in the same heap, having been picked over by the parodists, pastichers, and other artists who may not understand it, but are happy to use it for parts. And a mile beneath it is the even-more-ragged corpse of “Young Goodman Brown.”

In other words, this is all less of a critique of MBFE than it is a dirge for The Exorcist. I come not to praise The Exorcist but to bury it — which William Peter Blatty himself sort of already did, back in 1996, so, I guess we’re good.

Happy Halloween!

CORRECTION: The original version of this post inaccurately gave the publication date of Demons Five, Exorcists Nothing (William Peter Blatty’s satire of the production of the Exorcist movie) as 2015 instead of 1996. I went with the date listed on Amazon, which is always a mistake, especially with pre-2000 books. The New York Times regrets the error, which is weird, because they didn’t make it. Oh, and I regret it too.

Stuff I’ve been enjoying lately

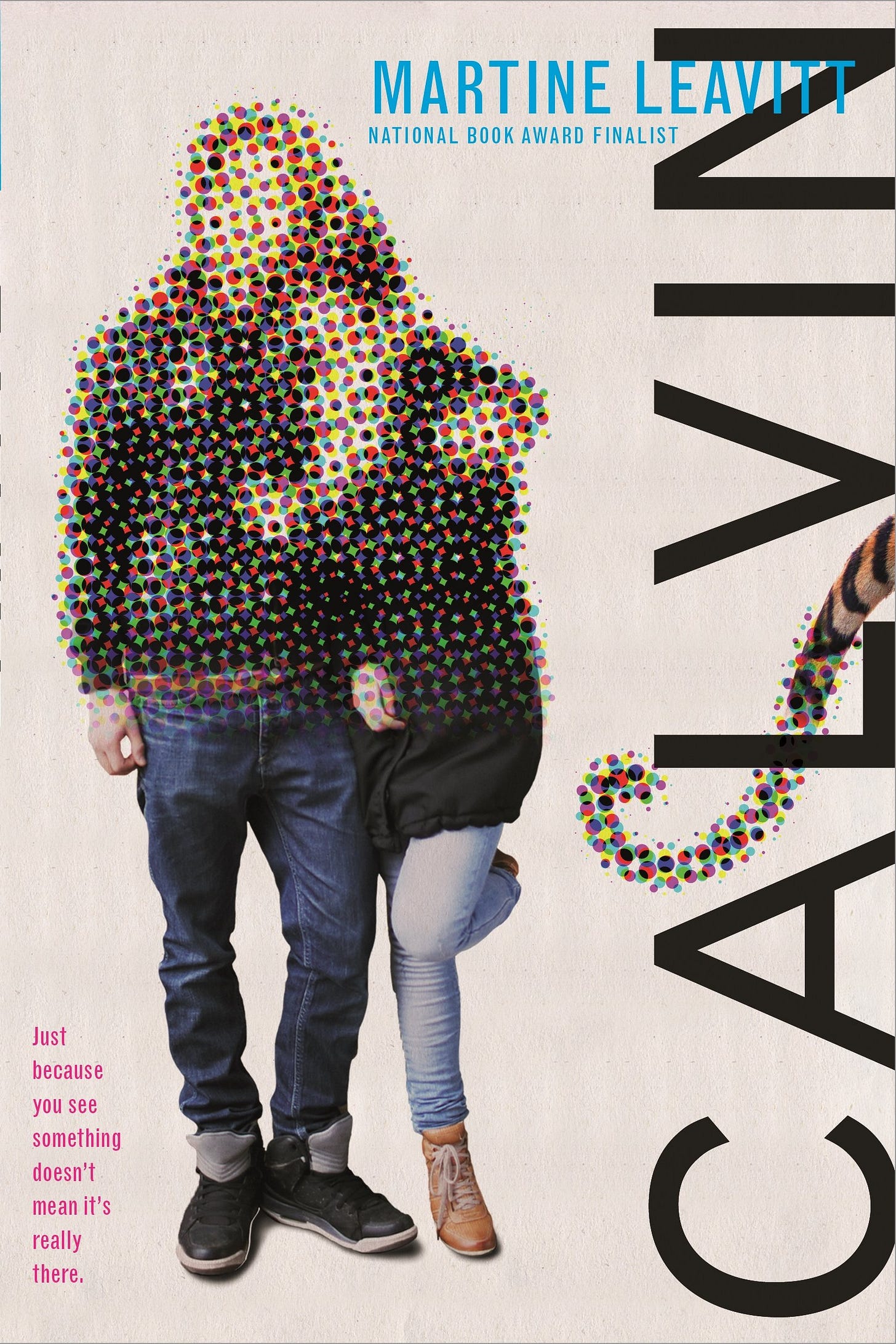

I actually just got back from vacation in Oregon a few weeks ago, and I managed to read three books in the week I was there (it was nice!). Two were MBFE and The Cult of Smart, both of which I mentioned above, but the best of the three was definitely Martine Leavitt’s Calvin, a YA novel that, for me, nailed the nostalgia thing in ways MBFE could only dream of.

The premise in this book is bizarre: the main character is a seventeen-year-old boy named Calvin who was born the day that the final Calvin and Hobbes strip ran. He’s a diagnosed schizophrenic who’s failing to banish his imaginary friend (a tiger named Hobbes, obviously) and has become convinced that his fate is somehow controlled by C&H creator Bill Watterson. If he can get Watterson to draw him one last cartoon, he thinks, his mental troubles will be solved.

Watterson lives in Cleveland and Calvin is in south Ontario, so the only thing standing in Calvin’s way is Lake Erie. It’s the dead of winter, so Calvin plans a “pilgrimage”: He’s going to walk across the frozen lake, track down Watterson on the other side, and demand one last cartoon. So he starts his trek, accompanied by his tiger Hobbes (whom he knows isn’t real) and his best friend Susie (whom he’s starting to suspect isn’t).

Calvin turned out to be an unforgettable blend of harrowing survival story and sweet fairytale, with a spare prose style that effortlessly evoked the loneliness of a Great Lakes winter and reminded me why I started writing in the first place. While there’s no denying that Calvin and Hobbes’s fandom — like every fandom — has become insufferable in the age of the internet, Calvin wisely uses the comic and its reputation as a jumping off point, instead of just endlessly hammering the nostalgia button.

Me, elsewhere

Speaking of Halloween, there’s a special Halloween episode of my podcast Changed My Mind up! I talked to Polygon editor Tasha Robinson about how she learned to love horror movies. This was previously a patrons-only episode, but I’ve made it available to everyone for free, because I like you.

Speaking of exorcists, I once got to interview an actual exorcist. Christian Tiews — an old friend of mine — used to be a agnostic, but eventually converted to Lutheranism, became a pastor, and started casting out demons. It was pretty interesting convo. Check it out here.

I’m done writing for Grunge, at least for now, but here are the last couple things I wrote for them: something about Jesus’s siblings, and a piece about the Book of Proverbs.