Little Shop of Horrors taught me everything I know about storytelling (and revision)

…no, really

Hey there, stranger! Welcome to my Substack. If you sign up to receive it in your email inbox, I’ll send you e-copies of both my published books for free. You can scroll to the bottom of this post for more info, or else just enter your email address here:

SPOILERS FOLLOW for all three versions of Little Shop of Horrors.

***

In December of 2009, I decided I was going to write a novel.

I’d made this decision for the same reasons I imagine most people do—I was bored, I hated my job, my English degree had rendered me useless to the world—but the main catalyst was my discovery of Victoria Lynn Schmidt’s self-help book Book in a Month. Schmidt’s method was revolutionary to me (especially since I had yet to learn about NaNoWriMo): I could bang out a draft of a book in 30 days, she assured me, if I kept moving forward, left out subplots, and didn’t backtrack or re-edit. Make the book “good” later; just get something on the page now.

I could do that, I figured. I’d start the thing January first (new year’s resolutions and all that) and bang out 300 pages by the thirty-first.

And…shockingly, I did it—and with a few days to spare, even. By early evening on the twenty-sixth, I was looking at a completed 75,000 words of literary horror—and the night was still young! I had some time to celebrate, and Netflix streaming had recently become a thing, so I popped some popcorn, climbed into bed with my laptop, and—for the first time—watched Roger Corman’s 1960 film The Little Shop of Horrors.

Seventy-two minutes later, I closed my laptop, thinking “…crap, I’ve really got my work cut out for me.”

***

Little Shop of Horrors—the 1982 off-off-Broadway musical—had, in my mind, always just been part of the Broadway canon. My parents had taken me to see a local production when I was ten (because, I assume, they enjoyed traumatizing me); one of the first CDs I bought at age fourteen was the original cast recording; when I took voice lessons in high school, one of the first songs my instructor reached for was the play’s show-stopping love song “Suddenly, Seymour.” Little Shop had just always been there, a platonic form no more or less essential than Les Misérables, Guys and Dolls, or Fiddler on the Roof.

But despite my familiarity with the stage musical, I was only vaguely aware of either of the film versions until my twenties. I didn’t get around to seeing Frank Oz’s 1986 adaptation of the musical until my junior year of college, and I somehow neglected Roger Corman’s original (non-musical) film until…well, the night I just described. When I finally saw it, I was mainly struck by just…how bad it was. How inexplicable it was that it had been remembered at all, let alone turned into a hit musical.

Most of the basic story ingredients were there—there was a flower shop owned by a crusty old guy, two employees, and a talking plant that ate people—but none of it worked. Nothing landed. It had twice as many murders in it as the musical (leaving out the climaxes, which I’ll get to in a minute)—but all of it just left me cold. It felt like I had just watched the quick-and-dirty, Book-in-a-Month-esque first draft of Little Shop.

Which was because, in a lot of ways, I had.

***

To talk about The Little Shop of Horrors—the original B-movie—we need to at least briefly discuss its creator, Roger Corman. Corman earned himself the nickname “King of the B’s”—and while he reportedly resents it, it’s hard to argue it’s inaccurate. Corman’s modus operandi throughout the 1950s and ’60s was to make movies so quickly and cheaply that it was almost impossible not to turn a profit on them. Often he would bang out a script on Friday, shoot it on Saturday, and edit it together on Sunday; if he got done early—say, Saturday afternoon—he would use the rest of the weekend and the dregs of the budget to crank out a second movie. None of that is a criticism, either; Corman was “punk” before “punk” was even an aesthetic, and he gave a lot of modern Hollywood staples their breaks (including Jack Nicholson, who made his debut with a small role in Little Shop).

Little Shop was no exception to this approach. The film came about because Corman had two days before the sets from one of his previous films, A Bucket of Blood, were scheduled to be torn down, and he figured two days was more than enough time to crank out another movie on them. He and his team started throwing around ideas for what they could make a movie about: A gritty police procedural? A comedy about a vampire music critic? Maybe a cannibalistic salad chef? Eventually, they landed on the man-eating plant angle, cranked out a script, filmed the thing, and released it. Like most Corman films, it turned a modest profit, and then disappeared from the public consciousness.

Or it would have—except Corman never bothered to copyright the thing, leaving it as fair game to anyone looking to fill out a UHF lineup or organize a cheap midnight screening. By the eighties, The Little Shop of Horrors was a certified cult classic—which was when Broadway legend Howard Ashman got his hands on it.

***

In many ways, Howard Ashman—who served as author, lyricist, and director for the original production of the musical—was the anti-Corman. Whereas Corman consistently aimed for “good enough,” Ashman was obsessive about fine-tuning every moment of his shows. As someone determined to revitalize the musical as an art form, Ashman was well aware of that Oh-no-they’re-going-to-sing-again feeling that even lovers of musicals can get when the orchestra swells for another unnecessary showstopper. Ashman understood that every emotionally charged moment—whether a song, a murder, or anything in between—has to have weight. It has to be justified by what came before it, and it has to affect what comes after it—otherwise, you end up with a theater full of people rolling their eyes.

If you’re unfamiliar with Ashman’s Broadway output, his commitment to detail is also clearly evidenced in three films you’ve almost definitely seen dozens of times: The Little Mermaid, Beauty and the Beast, and Aladdin—the three Disney films for which he served as lyricist and producer. When people talk about the “Disney Renaissance” of the early nineties, they’ll usually point to catchy tunes, lavish animation, or celebrity voices as the impetus for Disney’s comeback, but a careful rewatch of those films will reveal that their real secret to success was Ashman’s relentless efficiency in storytelling. There isn’t a single wasted moment in any of them: Every line of dialog moves the story forward; every action reveals something new about the characters; every song tells us something that words alone couldn’t. (The lone exception is the last twenty minutes of Aladdin, which, unsurprisingly, were substantially rewritten after Ashman’s untimely death.)

Ashman’s approach to Little Shop of Horrors was no different—which, when compared to Corman’s original, makes it something of a masterclass in how to revise and re-edit a story.

***

All three versions of Little Shop tell more-or-less the same story: There’s a flower shop on Skid Row, owned by a guy named Mushnik and staffed by a couple of kids named Seymour and Audrey. Attempting to drum up interest in the foundering store, Seymour puts a mysterious plant in the window—a plan that works great, until the plant starts demanding human blood, forcing Seymour to bring it sacrifice after sacrifice to maintain his newfound success. From there, things spiral out of control until Seymour himself is eaten by the plant. (In the musical, Audrey is eaten as well; Frank Oz’s film version tacks on a happy ending where they both survive.)

As I’ve said, though, the original film features twice as many deaths as the musical adaptations. In its hour-and-change runtime, the plant, Audrey, Jr. (renamed “Audrey II” in the musical, I assume because “two” is easier to rhyme than “junior”), eats a railroad security guard, a sadistic dentist, a would-be robber, and a prostitute. Each of these victims is onscreen just long enough to get killed and eaten; none of them contribute to the plot otherwise, and their posthumous absences aren’t really felt.

Just as importantly, though, every one of the victims dies more-or-less by accident. The railroad guard and the prostitute both die because Seymour is absentmindedly throwing rocks around, while the dentist and the robber both die in acts of clear self-defense (the robber is killed by Mushnik instead of Seymour, suggesting that Corman wasn’t super-clear on who his main character was). No doubt the intent is to keep the tone light and maintain sympathy for Seymour, but the effect is actually the opposite: because Seymour is just a schmuck having rotten luck, instead of actively making choices, the result is more distance and indifference than amusement or empathy.

Ashman’s adaptation, on the other hand, cuts the pre-climax bodycount down to two—the dentist and Mushnik himself—but it goes out of its way to make sure the viewer cares whether these two characters live or die. The role of the dentist—here named Orin Scrivello—is no longer just a random weirdo, but instead is Audrey’s abusive boyfriend. Further, Ashman makes it clear in the first handful of songs that Seymour and Audrey both yearn to be together, and only Orin stands in their way. Mushnik, for his part, is established as a lousy adoptive father to Seymour and the only thing between him and fame.

These changes complicate Seymour’s motives considerably, bundling up a bunch of moral quandaries with each murder. Is Seymour killing Orin to protect Audrey? To feed the plant? Or just to get him out the way? Similarly, is he killing Mushnik in self-defense (since Mushnik suspects him of Orin’s murder)? For years of verbal abuse? Or (again) because he stands in his way? There’s a clear progression here: First he kills Orin mostly-by-accident (after losing the nerve to do it directly); then he kills Mushnik deliberately in a moment of desperation. Similarly, while Orin is an obstacle to Seymour’s comparatively-more-innocent romantic ambitions, Mushnik is an obstacle to his significantly-more-cynical professional ambitions.

Ashman’s version takes Corman’s hapless klutz character and develops him into a hapless-klutz-turned-Macbeth-analog—a character swindled into trading evil deeds for success at the behest of a sinister force, slowly sinking into a moral morass as he does so. What’s striking, though, is that Ashman’s take isn’t any less funny than Corman’s for its insistence on taking murder seriously; rather, the contrast between the deaths and jokes makes both hit harder.

***

As it happened, the novel I had just banged out a draft of—Ophelia, Alive—wasn’t all that different from Little Shop of Horrors. It was another tale of a character driven to kill by a force (s)he was rapidly losing control of; like Corman’s film, though, my first draft was crammed with murders that were just there to fill up space and grope blindly for attention, like a bunch of exclamation points in a middle school essay. What comparing Corman’s version to Ashman’s threw into sharp relief for me was that body count isn’t what creates impact; impact is a result of the story’s events having weight, both in a moral and a structural sense. One compelling murder (or song, or anything else!) is a thousand times better than a hundred aimless ones.

Ashman’s version of Little Shop re-edits Corman’s in a dozen other ways as well—it removes unnecessary characters (Seymour’s hypochondriac mother and some Dragnet-inspired cops), takes away the plant’s hypnotic powers (…yep), and makes it clear what Seymour and Audrey yearn for early on (they want to escape Skid Row, as they tell us in the obligatory “I Want” song)—but all of these changes are, in the end, about making room for the audience to get to know the core characters so that both the highs and the lows land with maximum impact.

Did I implement these lessons in my subsequent revisions of Ophelia? Eh, I tried. I think I did okay. You can read the book for free and decide for yourself, I suppose. It was a first novel, so I was still learning as I wrote and re-wrote it—but whether I succeeded or not, what I definitely did was internalize Little Shop’s lessons and try to implement them more effectively with each subsequent novel. We’re all learning as we go, right?

And what you should definitely do, if you want to see how revision works, is watch Corman’s The Little Shop of Horrors and then watch Ashman’s version (a stage production, if you can find one—though Oz’s film is probably a serviceable substitution). It really is the perfect case-study.

And, in any case, it’s also about a singing, dancing, man-eating plant. So how can you lose?

Reminder: Subscribe to read both my books for free

Welcome to any new readers! I’m a horror writer and/or humorist out in Madison, Wisconsin. I’m working on building my audience, so if you sign up to receive this newsletter in your email inbox every month, I’ll thank you with free e-copies of both my published books. So that’s:

Ophelia, Alive: A Ghost Story, my debut novel about ghosts, zombies, Hamlet, and higher-ed angst;

Murder-Bears, Moonshine, and Mayhem: Strange Stories from the Bible to Leave You Amused, Bemused, and (Hopefully) Informed, an irreverent tour of the weirdest bits of the Christian Scriptures;

plus my monthly thoughts on horror novels, musicals, and the publishing industry; all for the low, low price of . . . nothing. It’s free. Why? Because I like you.

Click here for a bit more info about me, or enter your email address below to start reading both books right away:

Stuff I’ve been enjoying lately

Remember Shadowgate? If you’re between the ages of, say, thirty-five and forty-five, the odds are good-to-decent that you might; otherwise, you’re probably like, “Shadow-What-Now?”

Anyway, Shadowgate was a popular point-and-click adventure game originally released on Macintosh in 1987 (it later became a huge hit on NES in 1989), as part of a series of four similar point-and-click games. The other three (Déjà Vu, Dèjà Vu II, and Uninvited) have mostly been forgotten, but for some reason, Shadowgate developed a die-hard following that tries to create a sequel to it every five-to-twenty years. The original developer, ICOM Simulations, is long-defunct, but the property keeps getting passed around, resulting in an obscure 1993 sequel on TurboGrafx-CD, an even-more-obscure 1999 sequel on Nintendo 64, and an HD remake of the original on PC a few years ago. (My introduction to the series was actually the N64 game, which I imagine puts me in a very tiny club, since that game flopped hard. For fifteen-year-old me, though, the slow-paced, puzzle-based gameplay was a breath of fresh air on a console where nearly every game was about driving cars really fast or shooting people in the face.)

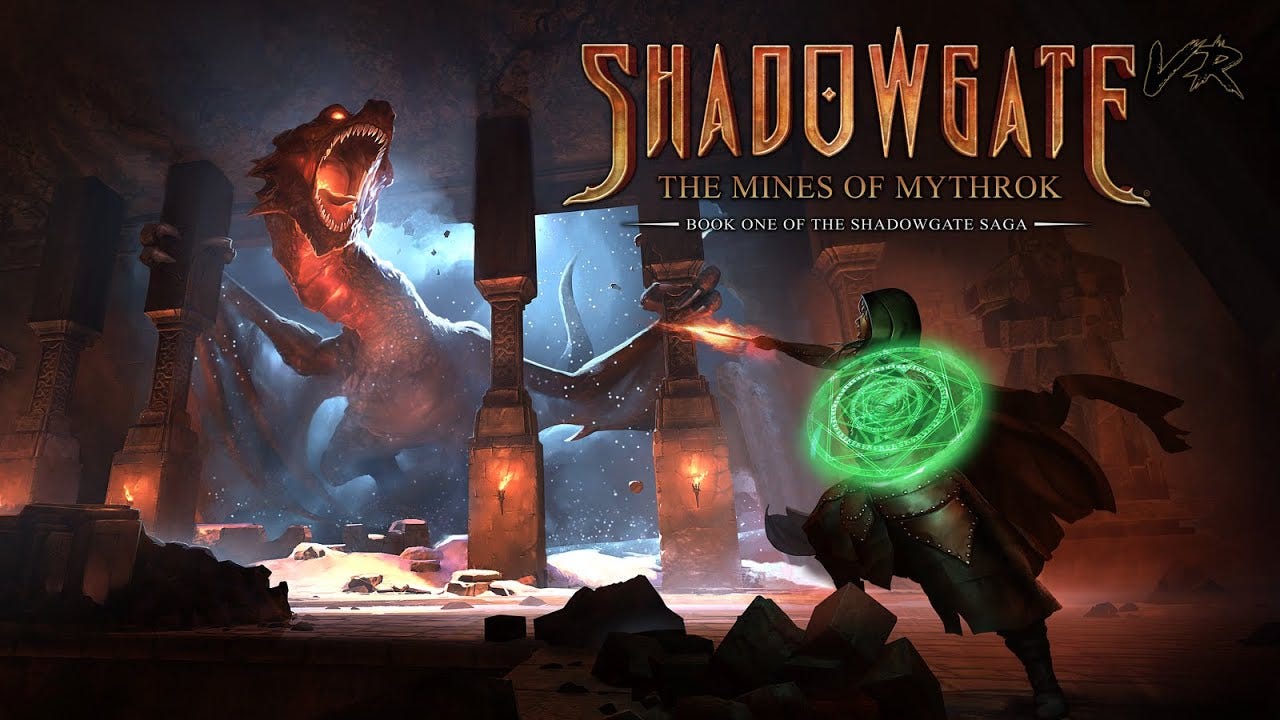

A few weeks ago, my wife brought home an Oculus Quest 2 VR headset, and while I was initially skeptical of it (TVs and computer monitors were good enough for my grandpappy, dangit), I thought I should at least give it a shot. I started poking around its online game store, and randomly came across…wait, a brand-new Shadowgate game? Made exclusively for VR? That I had somehow never even heard of??? What the what.

I went ahead and downloaded Shadowgate VR: The Mines of Mythrok, booted it up, and was immediately sucked in. Like the first Shadowgate, the focus is on making your way through a spooky location (an abandoned dwarf mine) by collecting items and solving puzzles with them—a process punctuated now and then by some pretty heart-pounding combat. For the VR outing, though, you’re in the middle of a fully 3D environment that invites you to look around and interact directly with it, and you’re accompanied by a very sarcastic talking raven who occasionally drops hints.

I’ve been having so much fun with Shadowgate VR that I’ve been forgetting to sleep. I’ll put on the helmet and immediately lose track of the world outside of these mines and this obnoxious raven (who is actually a very good boy who will let you pet him). I know everyone and their dog (and their raven) is playing Elden Ring right now, but if you get bored of that one and have an Oculus Quest, I really can’t recommend Shadowgate VR enthusiastically enough.