Is there a point to the Book of Job? I mean, sure, sort of

Ask a church receptionist #8

Welcome to another installment of Ask a church receptionist, a monthly column where I answer your questions about the Bible, Christianity, and whether “fetch” is ever going to happen.

Dear church receptionist,

What’s going on with the Book of Job? Am I supposed to take it as a true story, or is it just a parable? And if it’s a parable…what’s the lesson?

—Bible-curious

Dear guy who needs to cool it with the racy pseudonyms, because, come on, my mom reads this blog,

Anyone who’s been to Sunday school or read a children’s Bible story book probably knows the story of Job: He’s a rich guy who loves and serves God; God says, “Hey Satan, check it out, there’s at least one rich guy who’s on my team instead of yours”; Satan says, “Psshh, whatever, that guy only loves and serves you because you gave him stuff”; God says, “Cool story, bro; take away everything from him and you’ll see he’s still faithful”; Satan says “You’re on,” and proceeds to destroy all of Job’s possessions, kill his children, and strike him with horrible disease; Job still refuses to renounce his faith; God rewards him by replacing all his stuff. Happy ending!

But if you’re read the actual biblical book of Job, you’ll know that it’s…not that.

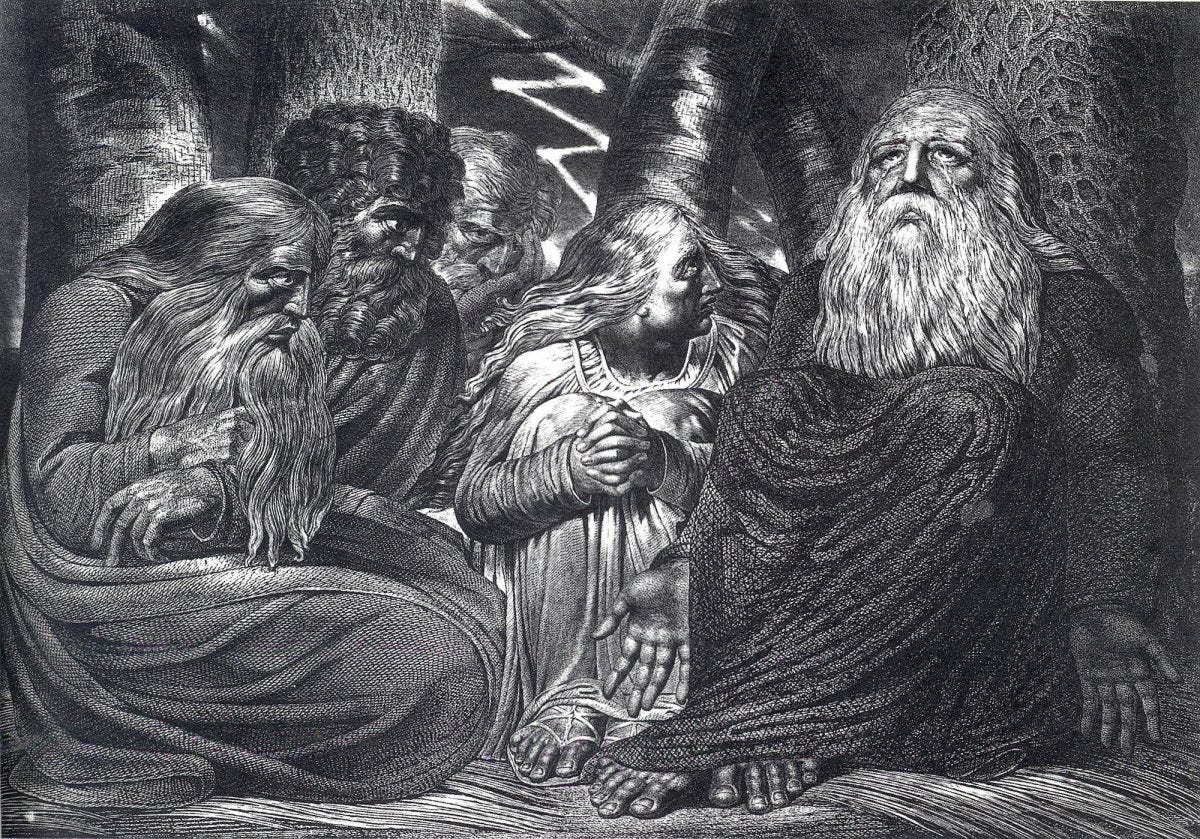

Don’t misunderstand me; the Sunday school version gets the basic story beats right, but the Book of Job is forty-two chapters long and nearly all of its “story” happens in just three chapters (the first, second, and last). The vast majority of the book comprises an extended debate between Job and his friends about whether or not Job deserves what he’s getting. Job’s friends say, “Hey, come on, Job, you must have committed some sort of horrible sin, or else God wouldn’t be punishing you”; Job says, “My dudes, I’ve done nothing wrong; why won’t God show up and at least let me plead my case?”; they go back and forth like that several times. Keep in mind that none of them know the cosmic backstory behind what’s happening, so it’s just a bunch of guys who like to hear themselves talk going on at length about things they know nothing about—essentially the prototype for the modern podcast. Finally, at the end, God does show up to announce that the discussion was sponsored by Squarespace he’ll hear Job’s case now—but more about that in a sec.

Let’s deal with the simpler question first: Is Job a true story? That depends on who you ask. Christian commentators, going all the way back to the Church Fathers, seem to have taken it for granted that Job was a historical person, but there’s a sizable Jewish minority who have historically had no problem taking it as a parable; the Babylonian Talmud (c. 3rd–6th century A. D.), for instance, contains a long debate between several rabbis as to whether Job ever existed—and, notably, when he did (the rabbis who insist on his historicity all disagree on when he lived, placing him all over the Old Testament timeline).

If you want my opinion on whether it’s true, I’d say sure, maybe, why not? Of all the stories in the Bible, “Guy loses everything and then whines about it” strikes me as one of the least far-fetched,1 so it’s a weird story to spend a lot of energy doubting; on the other hand, Job doesn’t really present itself as true, which is to say, the author makes no pretense of writing a history text. There’s nothing here that connects the events to any known historical events, and the fact that all the characters speak in spontaneous poetry suggests there’s at least a bit of embellishment happening. Which isn’t to say all of Job is made up—just that its historicity is far from the author’s primary concern.

What is the author’s primary concern, though? Or, in other words, what’s the “real” lesson to be learned from Job? Well, let me answer that with a couple of propositions:

Job is widely considered to be one of the “great” works of ancient literature, with scholars marveling at its beauty and power even to this day, and

You don’t achieve that status by offering people pat, easy answers to profound questions.

There are books of the Bible that have clear, unambiguous messages, such as Obadiah (“Edomites suck”) or 1 Corinthians (“Please stop banging your hot stepmom”), but Job really isn’t one of them. If Job wanted to teach a simple moral lesson, like “Patiently endure your suffering and you’ll be rewarded,” it could, but that version of the book would be only three chapters long and read like the Sunday school version. The focus of the Book of Job is on the debate, not the events, the explanation, or even the resolution. When God finally shows up at the end, the words he offers are neither comfort nor defense—just an indignant, “How dare you ask me for an explanation, don’t you know I invented the ostrich???” (Which…fair. Ostriches are cool.)

Job, like all great works of literature, is less a vehicle for a message and more a Rorschach test. The reader asks, “Why is there suffering?” and the Book of Job turns around and says, “Well, why shouldn’t there be suffering?”

I think there’s more profundity to that question than the average reader might realize at first. It’s easy for most modern Westerners to take it for granted that, if God exists, he’s a being of love who doesn’t think all that differently from how we do—but these assumptions come mainly from growing up in a culture that has conceived of God that way. If you start with the basic monotheistic conception of God—a being infinitely larger than the universe, knowing all and seeing all, able to bring galaxies into existence or snuff them out with a single word—well, why would you expect such a being to care about humans at all, let alone their highly subjective conceptions of fairness and justice?2 (How much time do you spend thinking about the moral convictions of termites?3)

Now—I’d say the opening and closing chapters of Job make it clear that God does take a unique interest in human suffering and human justice, but the focus of the book seems to be on how absurd it is to expect him to, especially in a way that satisfies whatever idiosyncratic convictions we may have. You’re free to agree or disagree, obviously, but I’d also add that one thing Job inarguably gets right is its implicit acknowledgment that there can be no good answer to the problem of suffering: For someone in the depths of despair, what possible logical answer could satisfy him?4 In that sense, the point of the book is less what God has to say and more that he chooses to show up at all.

That, by the way, leads into the uniquely Christian understanding of the book, if you want it: that God chooses to meet us, and even join us, in our suffering. The Christian answer to the problems raised by the Book of Job is found less in the final chapters and more in the Gospels, in the person of Jesus, who chose to put aside his universe-creating glory and suffer in the muck alongside us. I swear I’ll stop quoting C. S. Lewis so much in this column (maybe), but he put it quite memorably at the end of his final novel: “I know now, Lord, why you utter no answer. You yourself are the answer. Before your face, questions die away.”

I know people exist who disagree with Lewis about this stuff. But what answer would satisfy you?

Always suffering (mostly because weirdos keep calling the front desk to yell at me about how Christians are bigots and also Satan has possessed their dental fillings),

—the church receptionist 🕹🌙🧸

Got a question about the Bible, Christianity, or anything else for a real, honest-to-God church receptionist who literally wrote the book on the Bible? Send it to luke.t.harrington@gmail.com, or just click the button below:

(Be sure to tell me whether you want me to use your real name, a pseudonym, or whatever else.)

⬅️ In case you missed it: A short-short story about hippies and lighters

Free books have been shown to ease the suffering of existence

Hey, thanks for reading! If you’re new to this newsletter, here’s how it works: everyone who signs up to receive it in their email inbox gets free e-book copies of both my published books, plus you get entered in a monthly drawing for a free signed paperback copy of each! Why? Because I like you.

So, just for signing up, you’ll get:

Ophelia, Alive: A Ghost Story, my debut novel about ghosts, zombies, Hamlet, and higher-ed angst. Won a few minor awards, might be good.

Murder-Bears, Moonshine, and Mayhem: Strange Stories from the Bible to Leave You Amused, Bemused, and (Hopefully) Informed, an irreverent tour of the weirdest bits of the Christian and Jewish Scriptures. Also won a few minor awards, also might

…plus:

a monthly update on my ✨glamorous life as an author✨ (i.e., mostly stories about me lying around the house, playing videogames, petting my dogs, etc.)

“Ask a church receptionist,” where I answer your questions about the Bible, Christianity, and whatever else!

my monthly thoughts on horror, the publishing industry, and why social media is just the worst.

Just enter your email address below, and you’ll receive a weekly reminder that I still exist:

Congrats to last month’s winners, vauan4979d24g and marbleblackbooks! (If you are vauan4979d24g, please reach out to me! I’ve emailed you twice to no response!) I’ll run the next drawing Nov. 1! 🕹🌙🧸

I seem to recall Donald Trump doing this exact thing multiple times

Slightly famous comics author Benito Cereno once said to me, “Think about how hard it is to get people to agree on whether a hot dog is a sandwich. And if that’s the case, how can we ever hope to get people to agree on abstract concepts like justice?” I think about that a lot; every human on earth takes it for granted that his or her moral preferences are obviously the correct ones…but the only thing our systems of morality have in common is their mutual incompatibility

I’m obviously half-joking here, but consider that the differences between humans and termites are mostly finite, whereas the differences between humans and an infinite deity are (y’know, by definition) infinite

How many times have you heard someone roll their eyes at, or even rage against, trite sayings like “Everything happens for a reason”? Even if it’s true (and it is—the reason is the laws of physics), no one has ever been coaxed out of anguish by it.

I was excited to read this, because the book of Job is probably my favorite book of the Bible. It's also the one that started my re-conversion back to Christianity after many years as an atheist.

Like many atheists, one of my big problems with faith, especially a Christian faith, was the problem of evil. And I know it seems weird that it was Job that both cast that into sharp relief, and then also started to resolve it. I was also studying evolution at the time, and was engaged in a lot of very public arguments against creationism. (I'm still very convinced of the truth of biological evolution.) As I came to understand evolution better, and spent more time in nature, the last few chapters of Job made everything fall into place, in a way I can't really explain in words. It was just that the natural world is so beautiful, even with its bloodshed. I don't have to be able to explain everything. But I get to be a part of it.

Later, when I had more experience of suffering and our reaction to suffering, it became increasingly clear to me that this book is also, dominantly, about how we react to others' misfortune. Do we help Job bandage his boils, or do we come up with a well-reasoned explanation about why he deserves the boils? I don't have to be able to explain anything to be able to help, to love.