Mrs. Davis is the best thing on TV right now

…but probably not for the reasons you think

Hey there, stranger! Welcome to my Substack. If you sign up to receive it in your email inbox, I’ll send you e-copies of both my published books for free, and enter you in a drawing to win a signed paperback copy of each. You can scroll to the bottom of this post for more info, or else just enter your email address here:

***I guess this article technically has spoilers for Mrs. Davis? I feel like they’re all pretty mild.***

Simone the nun is in the Vatican, on a mission from God, and also a mission from an evil AI algorithm. It’s…a little hard to explain, but the mission itself is simple: Buy a cake. Bring it to the pope.

What sort of cake? She’ll know it when she sees it.

She enters the cake shop, the one Jesus himself told her to go to, and finds herself irresistibly drawn to a “king cake,” one of those ring-shaped pastries traditionally served on Epiphany, usually with a plastic baby Jesus hidden inside. “That one,” she tells the proprietor, who agrees to sell it to her—for one million dollars.

What?

Even if it weren’t for her vow of poverty, a million is impossible. She stumbles out into the street, and—desperate—tells her arch-rival, the all-knowing, all-seeing AI algorithm “Mrs. Davis,” that she needs the money and she needs it now. And then things start to happen: Strangers are walking up to her, handing her handfuls of euros. Soon Simone is at the door to the papal palace, million-dollar cake in hand, about to complete her mission. She’s on the guest list, she assures the guard. And she is—along with hundreds of other nuns, all of them sent on the exact same mission.

Simone is sick of being jerked around—by AI, by God, by anyone. “I am not the pope’s errand girl!” she insists.

Then she sits, alone, on the palace steps, stuffing her face with million-dollar king cake until she literally chokes on the Christ Child.

***

Peacock’s Mrs. Davis is a strange show—firmly in the vein of Roger Corman movies and underground comics, and also borrowing heavily from Her, 24, Indiana Jones, The Da Vinci Code, and maybe a bit of Jack Chick and 2000s-era CW dramedies. The premise, if you’re unfamiliar, is that a nun raised by Ayn Rand–loving magicians is sent on a quest for the Holy Grail by an AI algorithm (and also, concurrently, by Jesus himself)—and, based on that, you probably already know whether or not the show is for you. It’s very strange, and it’s also one of the best things streaming right now.

That it works at all is testament not only to its star, Betty Gilpin (who plays the absurdity with just enough winking, nodding, and eye-rolling to sell it), but also to how perfectly it vibes with something in the zeitgeist, or at least with something that’s been on my mind these days—namely, that we’re all sick to death of being jerked around by algorithms. We’re all tired of being digital cogs in the digital machine.

In an era of endless manipulation, how do you even know that you’re real? In the time of conmen, what even is “real”? How far off the grid do you have to go just to be able to think your own thoughts?

It’s a question that leads Simone from Reno to the Vatican to the belly of a whale—and finally into a death match with Mrs. Davis herself.

***

My Christian readers are going to be wondering just how heretical Mrs. Davis gets, and the answer is that, well…it’s not-not heretical? It might be roughly accurate to say that Mrs. Davis is heretical in the same way that that Disney Hercules movie is heretical: It plays fast and loose with the mythology, but that’s all it treats the ideas as: mythology. To Mrs. Davis, the tenets of Christianity are just one more thing to draw from—another prop in the cultural toy box, no different from the works of Shakespeare or an old advertising jingle. And that’s fine, I guess—Mrs. Davis isn’t the first time I’ve found myself loving something made by people who I’d guess wouldn’t respect me all that much.

But even that’s not a fair assessment of the show, because at the core of Mrs. Davis is a sincere grappling with the reality that countless people do have mystical, unexplainable experiences—and that they often find themselves profoundly changed by them.

In an extended flashback halfway through the series, we see the moment that changed Simone’s life: With her then-boyfriend gearing up to stupidly, pointlessly risk his life, Simone begins to do something she’s never even thought about doing before: she prays. She barely even knows who she’s praying to, but in that moment she finds herself transported—not to the gates of heaven, but to a run-down greasy spoon where a guy named Jesus serves a fine plate of falafel to anyone who walks in the door. And suddenly the old boyfriend is a distant memory. Simone is head-over-heels for this Jesus guy.

I’m not going to defend every theological idea proffered in Mrs. Davis (the show goes pretty off-the-rails in the last couple of episodes), but it might be worth pointing out that Simone is far from the first person to experience the love of God in a romantic or sexual way. Everyone from John Winthrop to St. Theresa of Ávila to King Solomon himself has drawn parallels between mystical and erotic experiences, so I’m not about to question Simone’s desire to get into Jesus’s pants—which she does, eventually, by taking her religious vows.

Some unspecified number of months after Simone and Jesus’s initial encounter, she finds herself stumbling into a convent outside of Reno. She equivocates for a moment, reluctant to tell the mother superior what she really wants, before finally spitting out: “Can you marry me to Jesus Christ?”

“Might I ask what is your faith?”

Simone hesitates. Her parents are Objectivists, atheists. “I’m not religious,” she says. “My parents always thought church was for chumps…”

“I didn’t ask if you were religious,” says Mother Superior. ‘What do you believe?”

“I believe I love Jesus more than I’ve ever loved anything or anyone in my entire life.”

I’ve never identified with a character more.

***

Simone grew up in Reno, surrounded by shysters and magicians—everyone she’s ever known has been a conman. It’s hard to think of a more perfect metaphor for our brave new “connected” world.

A couple of articles I read earlier this year have been sticking in my head. There’s this one by Ted Gioia, where he argues that AIs like ChatGPT are just virtual conmen—and if you’ve ever messed around with one, you know Gioia’s got a point. These AIs have no knowledge, no wisdom, no insight; all they’re able to do is spit out whichever sentences they think you’re looking for. If you argue with them, they’ll quickly reverse course and change their minds about all of it. Late in the series, Mrs. Davis makes the subtext text, telling Simone, “My users aren’t responsive to the truth. They’re much more engaged when I tell them exactly what they want to hear.”

In this article, though, Michelle Frederico argues that social media has turned all of us into the flesh-and-blood equivalent of ChatGPT. If you follow a new user on social media, you can see it happen in real time: They’ll start out by posting what they genuinely believe, but will gradually shift to doubling and tripling down on whichever things garner the most “likes,” “shares,” “comments,” etc. Pretty soon, they’ll even start to believe whatever nonsense they’re rewarded the most for saying.

This thesis explains so much about the internet: Why so many of our formerly normal friends suddenly believe absurd things. Why countless chat groups about (for example) “overcoming trauma” have instead become quagmires where people wallow in their trauma for years or decades. Why it’s so hard to put our phones down even when we’re getting nothing out of them. The internet—or at least the algorithms running it—is just a giant conman that’s turned us all into little conmen, all constantly trying to scam each other for clout.

And yes, “faith in institutions is at an all-time low,” as the pollsters love to tell us. How could it be otherwise, when all the think tanks, political parties, corporations, universities, and churches all have a finger to the wind, all constantly trying to pander to their most terminally internet-brained followers? From a certain distance, it looks like they’re all locked in a death match of trying to out-stupid each other, but the reality is even worse: they’re all trying to game the algorithms, when in fact the algorithms are gaming them. The house always wins in Reno.

We’re all just little conmen, and none of us can see it—except Simone. She gets it, because she was raised by conmen.

What do you do—what can you do—when the whole world’s gone insane for no particularly good reason? When even the thoughts in your head have been turned into digital cogs in a digital machine, to no end other than to keep the machine churning, to line the pockets of the digital billionaires?

I mean, there are moments when you want to just sit and stuff your face until you choke on that million-dollar cake. To rage against the machine’s nudges and predictions, just to prove you’re not a “piano key,” as Dostoyevsky’s Underground Man put it. But that’s not a real solution. To rebel against the nudges of the algorithm is to continue to be a slave of the algorithm, just in reverse. At some point, you have to find real meaning. Something to cling to in the sea of insanity. Maybe someone—a person who can bend to where you are, but doesn’t break in the winds of change for change’s own sake.

And, I mean, to that end, you can do a whole lot worse than that guy in the diner and his reliable plates of falafel.

***

I’m aware that not all of my readers here are Christians. Probably a lot of you read that line about Simone loving Jesus and feel your eyes rolling instead of your heart bursting. And that’s fine—in the moment, it’s clear that Gilpin’s Simone is aware of how cringey the line is, even as she says it. “I love Jesus” is another trite cliché, another tool in the toolbox of conmen.

But I dunno, man. I’ve never met anyone who’s actually taken the time to read the gospels and wasn’t fundamentally changed by them in some way. I’ve never heard of a part of the world that hasn’t been altered, in one way or another, by the teachings of Jesus. And maybe it’s all just smoke and mirrors. Maybe Jesus is just another magician, another conman. Certainly conmen the world over have made extensive use of his teachings to their own ends.

But here’s the thing: one by one, all those other conmen have fallen away, consigned to the dustbin of history. Jesus is still around. People are still reading the guy, still having their lives changed by the guy. If he’s a conman, he’s the greatest conman of all time.1

At the very least, you have to respect that.

***

This isn’t what you might call an “evangelistic” article. I come here to praise Mrs. Davis, not to praise Jesus. (Or, for that matter, to bury him—which, historically, has been shown to be a futile endeavor, anyway.)

We just passed the one-year anniversary of my own spontaneous retirement from social media, which might be part of why the character of Simone resonates so deeply with me. My initial article about quitting Twitter, Facebook, and the rest generated high enough readership numbers that I revisited the topic several times—making me wonder if perhaps I was still falling victim to the insatiable algorithm, letting my audience dictate my convictions, instead of the other way around.

I’ve mostly kept the original commitment I made in that initial article, though—one to scroll feeds less and pray more. Sometimes that’s taken the shape of praying the Liturgy of the Hours, but lately I’ve been keeping things even simpler—just sitting on the floor of my office, intoning the Jesus Prayer, over and over. It’s not exactly carnal acts on the floor in front of the falafel fryer, but it’s not not that, either. What it is, is me reaching out for a connection—a real connection, the sort of connection you’ll never find in the ephemerality of the algorithm. As my fellow social media skeptic Ian Bogost once put it: “a stillness of connection, a bridge that goes unused.”

In a former life, I used to host a podcast called Changed My Mind with Luke T. Harrington. At the end of every episode, I would get pretentious and ask my guest, “What is truth?” More than one of my guests—usually one who had converted to one flavor of Christianity or another—smiled and told me, “Truth is a person.” Even if you disagree, you can understand the appeal of the idea: If The Truth™️ is nothing more than a set of facts, you’ll never know it—there are too many people making too much money by keeping those facts from you.

But a person? You can know a person.

And a person can be True—not in the harsh, unyielding way that facts are, or in the slimy, sycophantic way that an algorithm is, but in a real way. A way that can be tested, over and over, ever more deeply, even as the years and decades and eons go on.

And I guess that was what spoke to me about Mrs. Davis—its willingness to engage with questions of what truth is, or can be, in an age of algorithms, and how profoundly unsatisfying this brave, new, constantly-connected-for-no-good-reason world is, and why some of us are choosing to opt out of it, and seek meaning in older, deeper, and realer places.

Of course, most of the time, it wasn’t doing that—it was just being balls-to-the-wall wacky. But maybe, in an era plagued by starry-eyed digital cynicism, balls-to-the-wall wackiness is the only way to say anything True™️ and not have the masses roll their eyes. 🕹🌙🧸

Free books, with no late fees!

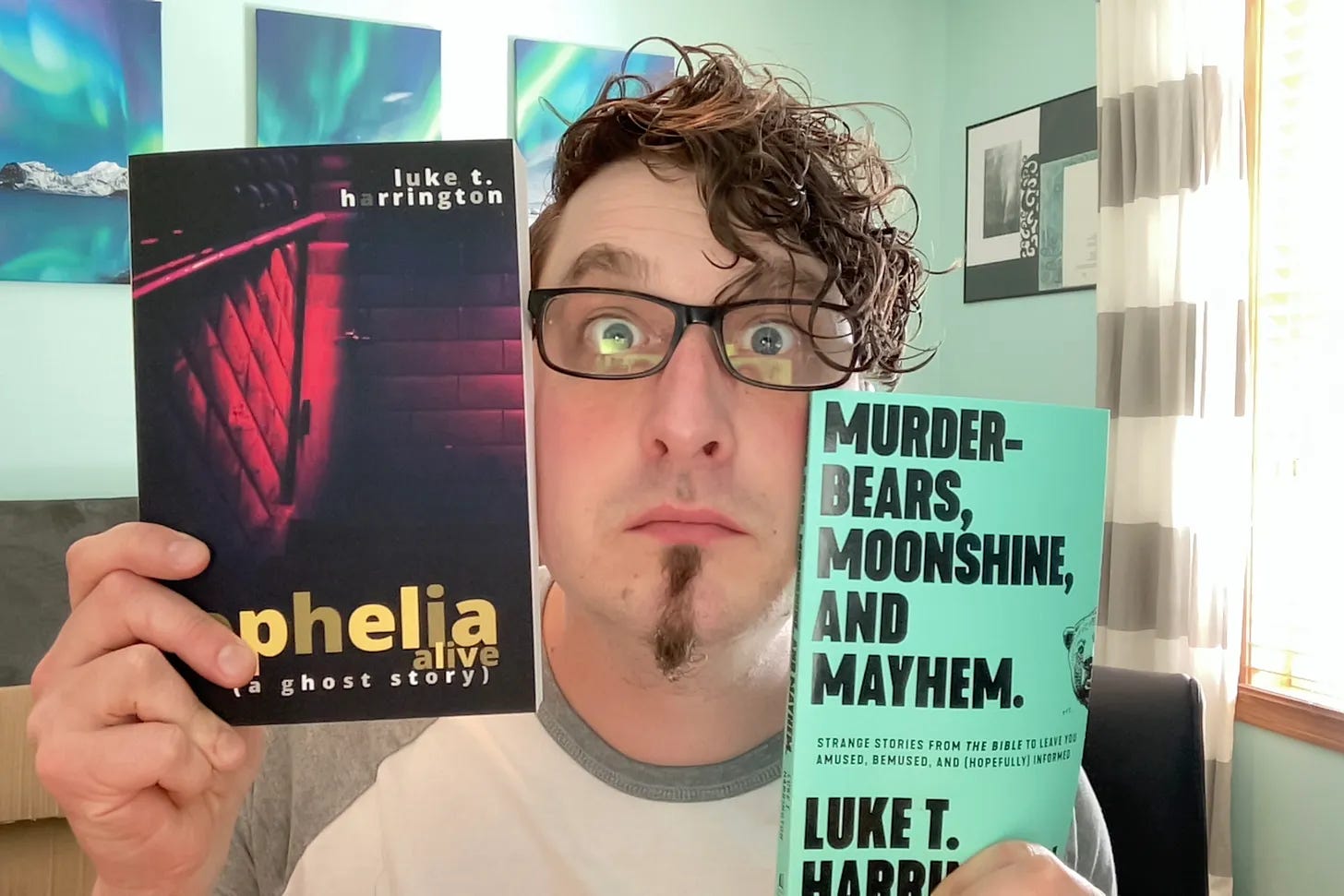

Hey, thanks for reading! If you’re new to this blog, here’s how it works: everyone who signs up to receive it in their email inbox gets free e-book copies of both my published books, plus you get entered in a monthly drawing for a free signed paperback copy of each! Why? Because I like you.

So, just for signing up, you’ll get:

Ophelia, Alive: A Ghost Story, my debut novel about ghosts, zombies, Hamlet, and higher-ed angst. Won a few minor awards, might be good.

Murder-Bears, Moonshine, and Mayhem: Strange Stories from the Bible to Leave You Amused, Bemused, and (Hopefully) Informed, an irreverent tour of the weirdest bits of the Christian and Jewish Scriptures. Also won a few minor awards, also might be good.

…plus my monthly thoughts on horror, the publishing industry, and why social media is just the worst. Just enter your email address below, and I promise I will not attempt to recruit you into some sort of sinister cult (probably):

Congrats to last month’s winners, swirsky and jordanpolingarnold! I’ll run the next drawing June 1! 🕹🌙🧸

Stuff I’ve been enjoying lately

When my youngest daughter caught me reading Howard the Duck: The Complete Collection, Vol. 1, her reaction was kind of priceless: “You like Marvel???” she said, eyebrows going up.

Well…no, not exactly. The MCU does absolutely nothing for me (though I feel I’ve given it plenty of chances), and I’ve never been a huge comics aficionado in general (I have nothing against comics; I’ve just never really gotten into them in a big way), but every once in a while, something does grab me. When I finally got around to Howard, well…I sorta fell in love with this cranky little duck.

These days, Howard is mainly remembered for his famously terrible 1986 film (the first Marvel movie ever made [!], produced by George Lucas [!!]), and he occasionally makes cameo appearances in other Marvel movies (mainly in the Guardians of the Galaxy films), but his initial run in the 1970s was truly something to behold—one of the very earliest cases of a major comics company just giving their weirdest writer free rein to write the weirdest stuff he could imagine.

For the uninitiated, Howard lives in the same shared universe as heroes like Spider-Man and the Hulk, but he’s…just a duck. A three-foot-tall anthropomorphic duck who loves cigars and never encountered anything he wasn’t mildly bored by. His series is sort of a parody of Donald Duck comics, and sort of a parody of Marvel superhero comics, but mainly it’s just absurdist weirdness for absurdist weirdness’s own sake—the sorts of stories where you’re encountering a mental patient possessed by the rock band KISS, a gingerbread Frankenstein monster, and a cult of thinly veiled “Moonies” within a few issues of each other. If there’s a point to it all, it’s that—according to an oft-quoted line from series creator and writer Steve Gerber—“Life’s most serious moments and most incredibly dumb moments are often distinguishable only by a momentary point of view” (a sentiment echoed by Mrs. Davis in many ways).

It’s actually a little more than that, though, because two-thirds of the way into the first volume, we get a pretty unflinching and sympathetic look at mental illness, albeit through the eyes of a duck. Self-consciously “serious” comics are a dime a dozen these days (not literally, comics are expensive now), but it’s clear that Howard waddled so they could run. I look forward to picking up Vol. 2. 🕹🌙🧸

Then again, maybe I should also acknowledge the Buddha, who’s been “conning” people several centuries longer