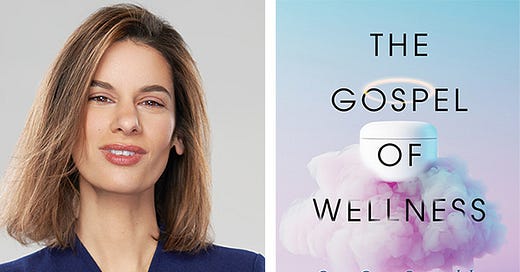

“I kind of blew up my career to write this book”: an interview with journalist Rina Raphael

‘The Gospel of Wellness’ is out today

Hey there, stranger! Welcome to my Substack. If you sign up to receive it in your email inbox, I’ll send you e-copies of both my published books for free, and enter you in a drawing to win a signed paperback copy of each. You can scroll to the bottom of this post for more info, or else just enter your email address here:

This piece is pretty different from what I usually publish here, but I got handed an opportunity I couldn’t say no to: Journalist Rina Raphael, who apparently was a fan of my now-defunct podcast, reached out to ask if I’d like to write something about her debut book, The Gospel of Wellness: Gyms, Gurus, Goop, and the False Promise of Self-Care. I read it and found it thoroughly researched, sagely insightful, and often laugh-out-loud funny. I asked Rina if she’d give me an hour of her time to talk about the ideas in the book, and she graciously agreed. So thanks to Rina for the book and the interview.

I highly recommend that you help me thank her by buying her book, which you can find at Amazon here.

Interview has been edited for length and clarity.

The book is about the “wellness industry.” For readers who might not know what the wellness industry is, can you sum it up?

First of all, I think the term “wellness” is really confusing for the average consumer, because it can seemingly encompass everything. It’s the pursuit of “health,” but that can include everything from nutrition to meditation to fitness to crystals to spiritual gurus. That’s the problem, and it’s the distinction I make in the book: What is actually helping us be healthy?

And “healthy” is a term literally no one can define—when are you “healthy” enough? It’s a very bloated industry that keeps shoving more and more things under its umbrella.

So that’s what’s become of the wellness industry: anything can be sold now telling you that it’s going to make you healthier, fitter, better, prettier—whatever it is. And that’s what I think people are getting very, very tired of. I think I mention in the book that there are reports coming out that every brand is going to try to be a wellness brand. And it’s kind of serious—you actually have the auto industry doing aromatherapy or guided meditation in their cars.

I think you mention in the book—what kind of made my eyebrows shoot up the most—is that apparently Amazon is sending customers emails about what the best products for them are, based on their horoscope. That’s a thing now? I had no idea.

Yeah, I called them out on that in Fast Company. Don’t ask me why I subscribed to Amazon Prime’s newsletter, but I did. When I saw it, I was just so flabbergasted by it. I don’t know if they still do it, after I called them out on it. And of course it was written by someone who didn’t seem—I mean, don’t want to knock people who believe in astrology, but I don’t think it was a famous astrologer. I think it was just some fashion writer, writing about how Scorpios need to practice communication with their Alexas—it was absolutely outrageous.

But this stuff works! If you go on any women’s retailer website, like Anthropologie, they’re selling, like, crystal-infused face rollers that will help “renew your sense of being”—it’s such useless terminology. And I think it worked for a while, but I think right now you’re seeing a smarter consumer who has sort of drunk the Kool-Aid on this stuff—bought a whole lot of CBD chemicals and crap, and none of it worked, and it’s crowding their bathroom counter, and they’re tired of it.

So the wellness industry, I see, is already moving forward. I have a piece in the L. A. Times that’s about how we used to see far more ridiculous products come out—like CBD leggings or toilet paper. And consumers just aren’t buying that shit anymore. I think the pandemic really forced the average woman to think about things like, “What is real health? Where am I getting my health information? Do I really need all those fancy green juices? Because I’ve been home for six months, and I’m just fine without it.”

Beth McGroarty, who’s a research director at the Global Wellness Institute, has a really good example where you buy CBD cream and you’re like, “Is this working? I don’t know if it’s working, but my friend says it’s working.” You almost have to convince yourself. And this is why it’s often so hard to convince someone out of a wellness belief—because it’s not really based on scientific evidence. It’s based on hope, on aspirations, on wanting to look like Gwyneth Paltrow. You want to convince yourself. So you’re not dealing with logic, you’re dealing with psychology.

Yeah, I can say, from my personal perspective: I’ve actually gotten to a point where I feel about a thousand percent better than I did a year ago—since we’re talking about wellness—but it was kind of shocking to me how stupidly simple it was to get to that point. I stopped eating junk food, I started lifting weights every day, I got off social media.

You didn’t need crystals and a fancy gym membership and all that shit?

Yeah, nah, feeling better is stupidly simple. Just buy some weights and lift them.

Or just go out and walk. But there’s no money in telling a consumer to go for a walk.

Right.

That’s the problem. I touch upon this briefly in the book, but what we have in America is a phenomenon that’s not replicated in any other country. You don’t have countries who are looking at wellness through a prism that’s so individualistic, where it’s on you to do everything, versus saying, “How can there be communal solutions? How can the government support me? How can my insurance support me? Or the healthcare industry?” It’s so consumerism-driven. It’s so tainted by this Puritan work ethic, like you have to work hard to be healthy. It’s fetishizing health,—it’s no longer just a normal part of life. It’s like, “Ah, my boutique gym! Ah, my green juice!” It’s not normal.

I was speaking to an academic who studies this in Italy, who was like, “I don’t think our country needs as much wellness. We get six weeks mandated vacation every year. We have two-hour lunches. Your boss doesn’t email you after work. Like, you guys are the crazy people. And also, we don’t solve things by buying a whole bunch of crap.” So what we see here is very, very American.

I appreciated how you talk about how this American milieu we live in—the culture, the economy—seems almost custom-designed to make people as miserable as possible. There’s so little community. We work such long hours for such little pay. We’re constantly bombarded with messages about how everything is terrible from television and social media. And it’s like, if you don’t feel well, that’s probably why.

And I think men are hurting too, but it feels especially visceral for women, at least according to my research. Women really feel things are out of control, for a number of reasons—Roe v. Wade is a perfect example of women feeling powerless, but even just the burdens that are foisted on women from a body image perspective, too. There’s a reason women are really fueling the diet industry, more than men, why they fall for these diet gurus: because they feel like they have to be a certain size. That’s nothing new, but you take that, and then you couple in things like these very paltry childcare policies in many states. Women have to deal with a lot more—and they’re targeted more by the wellness industry.

For example: Go to a women’s website and type in the word “toxic” and you’ll get thousands of articles about “Your kitchen is toxic! You beauty products are toxic! Your vibrator’s toxic!” and women are in a panic: “Oh my God, I have to make sure my kid doesn’t get cancer, because everything’s toxic in my home!”

You go to a men’s health website—I don’t know if this is true, I haven’t done this, but I’d guess—if you type in the word “toxic” it’ll probably be an article using the word “toxic” to describe your relationship with your boss. It’s not the same thing.

So men aren’t targeted the way women are. I’m terrified of everything in my house, and if I try to tell my husband about it, he’s like, “Yeah, I think my Mitchum deodorant is fine.” So women are targeted more, and they’re targeted more because they’re in charge of more things—they’re in charge of the family. Especially young moms are targeted.

At the end of the book, I talk to Food Science Babe, who’s a food scientist and influencer. She talks about how she was in meetings where the marketing department was like, “We’re gonna target young moms. We can make them terrified”—even though the product wasn’t based on science whatsoever.

So it’s no wonder. I’m here in L. A., and I can’t tell you how many times I’ve had dinner with couples where the woman’s going on and on about organic, and non-toxic foods, and the husband’s just sitting there going, “I don’t know anything about this.” Of course he doesn’t know anything about it. It’s because he’s not targeted. It’s not in every one of his publications. It’s not in his Instagram feed. He doesn’t get that shit. It’s a very misogynistic industry, and I don’t think women realize it. It’s using a lot of the same tactics that the beauty industry used fifty years ago.

You contacted me, originally, because of my show Changed My Mind, and you mentioned that you used to be deep into this stuff. Can you tell me a little bit about that story—how you fell for it, how you got out of it?

I’m pretty forthcoming that I felt pretty miserable in New York City, even though it looked like a kind of dream life. I was working for NBC News. I was single. People thought it was a great gig to work at The Today Show.

You were like the lead in a romcom.

Totally. But I was really lonely, and I was really exhausted—my job really did not end at the end of the work day. I was in charge of five different verticals. Anyone who works in media now knows that they have to be a writer, an editor, a trendspotter, a newsletter writer, a director—like, it’s everything—while also being terrified of where the industry’s going. I know this is very specific to people who are in media, but I wasn’t really happy.

And what did the wellness industry promise? It promised solutions. They said, “Oh, you need a community? You’re tired of herding cats every time you want to make dinner plans with friends? I’ll just make sure you’ll see people three times a week at your local gym! Oh, you’re exhausted? I know some gummies that will give you all the rest that you need! Oh, you don’t have enough energy? We need to change your diet!” Any problem that you had, they were selling the solution. And I wanted to believe in them.

Also, they used so much scientific lingo. I mention in the book how they use terms like “clinically tested”—all these vague terms where if you’re not actually educated about marketing tactics, you’ll fall for them very, very quickly. So I fell for all these things. I “ate clean,” which gave me disordered eating; I cleaned out my entire beauty counter and only bought “clean” products without really understanding the science behind it—because this was given to me at every single outlet. Every single outlet was telling me the same exact thing.

And then when I moved to Los Angeles—because I really thought they had a better lifestyle, because they went jogging year-round, and they drank the green juice, whatever that is—I became a full-time wellness industry reporter for Fast Company Magazine, and I will say now that I contributed some misinformation about a whole bunch of trends and products. I really touted a bunch of startups that I wouldn’t today. I wrote, like, eight-to-ten articles a month—and I would be called out by scientists and doctors on social media, saying, “That is completely incorrect, why would you think that?” and I would say, “Well, because it’s everywhere!” and they would say, “Well, maybe everyone’s wrong.”

And this is the problem, I think. We hear about misinformation, and how it comes from Gwyneth Paltrow and crazy antivaxxers, but it’s also coming from legacy media. It’s also coming from top publications that all bought into it—and that’s because wellness is treated a lot like fashion by the media industry. It’s not put upon them to really investigate claims, it’s just taken as a given: Of course organic is healthier! Of course clean beauty is right! Everyone’s just mimicking and echoing everyone else.

And so, there’s the convergence of two things. One is I realized that the way I was living my life was not making me better—it was making me more stressed, more paranoid, more terrified of everything—and I was spending so much money on my “wellness lifestyle.” But also, I was being called out by scientists and doctors who actually knew their shit. So it really forced me to step back and say, “What am I devoting my career to? What is really the truth? And at the time, I was the first wellness industry reporter, so I kind of blew up my career to write this book.

And I don’t regret it—right now, I’m friends with all the science-based influencers on social media—but misinformation is a problem everywhere. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve heard from people who say, “I’d love to interview you, I’d love to have you in our magazine, but we also really depend on supplement ads right now, and I know they’re bullshit, yeah, but your book attacks them.” I mean, that’s what we’re living in. The wellness industry has so much money, and it’s fueling all these women’s publications.

And because, again, wellness is treated like fashion, people don’t actually realize that they should be checking with experts. A reporter will tell me, “Oh, I checked with a dermatologist”—but I’ll say, “But you’re dealing with toxicology claims. You should be speaking to a toxicologist. A dermatologist is not trained in toxicology at all.” So I think most reporters are put on the wellness beat, but they don’t have a scientific background. So I really learned my lesson—anything I report on now, I speak to like five different experts. Because I got burned.

So over the last five or six years, I’ve been increasingly aware of this strain in American culture that I wasn’t before—or at least hadn’t thought about that much. Where it started, for me, was in 2016 when Donald Trump was running for president, and people were saying, “How can evangelical Christians love this guy so much? He’s clearly not a Christian!” The answer I heard, from several sources, that made the most sense to me was “Y’know, he’s actually not that far removed from, like, the big tent revival preacher.” Right? Like, he’s not preaching about God, or whatever, but he’s spouting the same sort of flimflam, working the crowd the same way.

And once I heard that, I started seeing this same thing everywhere—that the essence of a lot of American culture is the flimflam man. The huckster. Y’know? And there are hucksters that appeal to the sort of people Donald Trump appeals to, but there are hucksters who appeal to the progressive upper classes as well. And I guess I just wanted to ask you about that—is this a uniquely American thing? Is it inherently a bad thing? Is there anything that can be done about it?

Well, throughout the book, you’ll see that I flash back to gurus of the past.

Which I really appreciated.

I always say there are four unique trends that got us the wellness industry, but one of them is the fact that we’re dreamers in this country. We’re a nation that put a man on the moon. Our ancestors ventured out west to seek their golden fortunes. We built Hollywood based on these Disney endings. We love the fantastical, the aspirational, the “If you can dream it, you can will it.” And on the one hand, that gave us Hollywood. It gave us Silicon Valley. It’s why America’s so successful. We’re crazily optimistic!

But the drawback of optimism is gullibility. We’ve always fallen for hucksters because we want to believe in the transformational and the aspirational—“We can do it! We’re doers! We’re Americans!” And that’s how we got Donald Trump, and that’s how we got Gwyneth Paltrow, and that’s why we keep getting all these supplement influencers. It’s kind of built into us. So there are amazing things about being overly optimistic, and there are some bad things.

And that’s why I say the wellness industry is based on belief. It’s based on thinking, “Oh, if I take this supplement, I’ll be just like Gwyneth, I’ll be beautiful like her”—without realizing it’s probably her genetics.

And I fell for it. It told me it could cure my sleep problems, my energy problems, everything. And women want to believe it because they’re desperate—or they think they are. I wasn’t a sick person, I had no chronic diseases—but I didn’t feel well. That’s who they’re targeting. They’re not actually targeting the people who are really sick.

Because those people don’t have money.

No! It’s dissatisfied rich women—I mean, I’m half-hispanic and half-Jewish, so I definitely have other things I’m concerned about—but yes, they’re targeting people who have income to spare. And I fell for it. And they’ve also realized that men aren’t going to fall for it the way women will, because women are subject to unique pressures.

I do want to poke at that a little bit, though—because the whole time I was reading the book, I kept thinking about Alex Jones and people like him. And then eventually I got to the part where you mention Alex Jones. And obviously the book is written from a female perspective, and for women, but as you mention in the book, a lot of the supplements that Alex Jones hawks on his show are identical to what Gwyneth Paltrow is selling—

But Gwyneth charges a lot more.

Well, that’s what was interesting about it to me, because obviously Gwyneth Paltrow is this figure who appeals to upper-middle-class women, while Alex Jones is going after lower-class men—but they’re selling the same bullshit. What does it say about us that both the left and the right, both men and women, are so eager to believe the exact same bullshit?

I don’t deny that men are also preyed upon—I think there’s an entire chapter about the biohacking movement, which is really, really targeting men. But if it says anything, it’s about that optimism thing again. When you fall for optimism, you fall for quick fixes. So of course you fall for a supplement—like, “Why would I want to do the work of eating well and moving my body, when I could just take a pill?”

And this is also because we’re accustomed to things like antibiotics—which really were magical pills that could cure you in a heartbeat. But those are different from supplements. Supplements are not tested for efficacy by the FDA—the FDA just double-checks that they’re not going to kill you.

So I don’t ever say that supplements are something that are just being targeted to upper-middle-class women. Supplements are used by all Americans, a high percentage of them. And I wouldn’t say all supplements are bad for you—obviously, if you’re working with a doctor and you’re missing something, that’s a different story (like vegans might need B-12, for instance)—but the majority who take supplements don’t need them.

But they see marketing saying “You’ll have more energy, you’ll sleep better”—and they want to believe it. Because the alternative isn’t that attractive.

I was really struck, reading your book—and I guess I’ve just become increasingly aware, in the Trump era—of how much of this is ultimately about class. Karl Marx wrote a bit about what he called “the morality of the petite-bourgeoisie”—the need of the professional class to advertise that they’re the “right sort of person” in order to maintain their tenuous hold on privilege—how much of “doing the right thing” is about signaling to those around you that “Hey, I’m one of the good ones, I’m doing what I’m supposed to do.”

I mean, it’s totally an identity. And I think those are two different questions of people signaling what they get out of it, versus those who are most in need of actual health initiatives—people who don’t have access to healthcare.

I will say that there is a naïveté about what the lower income classes actually need. They’re so stressed. They’re working two to three jobs. They don’t have any time. But what I often hear from my friends is, “Oh, they live in food deserts. We need to give them more vegetables.” And who’s going to cook them? Who’s going to prepare them? Or “They just need more gyms!” But how will they have time to go to the gym? It’s so naïve.

I even get into the spiritual market—you talk about something like manifestation, which is huge with upper-middle-class women right now, especially on social media—

Like The Secret, and stuff like that.

Right. And you don’t see manifesters going into lower income communities and saying, “You just need to think your way out of this.” They’re appealing to people who already have their basic needs met, who just need that fine-tuning, who just need that perfect husband, or that perfect house, or that perfect promotion. That’s what they’re targeting, and that’s what’s so frustrating about it. And these people will go on and on about how much they care about diversity and how much they care about other groups, but it’s complete bullshit.

And in some ways, they’re hurting people. When you have all these companies and all these influencers talk about how conventional produce is bad for people—what it ends up doing is terrifying lower income communities from buying produce that they desperately need. Because they’re terrified of these toxins and pesticide residues, which are only present in trace amounts—they’d have to eat 8,000 nectarines a day to see any effects. That’s the problem with this entire thing, is that it’s really leaving out certain groups, and it’s based on complete bullshit.

I think you talk a little bit in the book about how the faces you might see on your Peloton are “diverse,” but I think you call it “curated diversity”—where it’s maybe racially diverse, but not economically or ideologically diverse. It’s this imaginary world where everyone is just an upper-middle-class progressive.

Right, where everyone thinks like you. I think I’m quoting Maria Doerfler, who’s a Yale religious studies professor, who says it’s “a very curated type of diversity”—I don’t remember the exact quote—but yeah, it is. They all think like you, and look like you, and act like you. And you really think that you’re engaging with your neighbor, but you’re not. Like, get out of your house, go to another neighborhood in your city, and really engage with people! “But we don’t wanna do that!” Right? “We want someone who looks and acts like us, someone who’s gonna work really hard on their bike.”

So, that’s kind of the problem. And this is where I think that people are really kind of tricking themselves. I mean, I fell for it too, and in my book, I incriminate myself all the time. I talk about literally licking the sugar off Sour Patch Kids [because she was starving due to a fad diet]. My editor was like, “Please don’t put this in!” but the truth is that I fell for this crap too. I hate how much of this discourse is about women who fall for Goop, or women who are into wellness and how dumb they are—because they’re not dumb. It’s just that the branding and marketing are so seductive, and they’re people who feel very, very desperate. And I have a lot of compassion for them.

And I think it says something, although I’m not sure what, that so many of the people falling for stuff like this are people putting signs that say “Science is real!” on their front lawns.

Well, here’s the thing: Science is not facts. Science is not truth. Science is a process, and so we’re always finding out new things. So that bothers me too, the way that we even discuss science. But I have people all the time who will say, “Trust science!”

And I’m like, “So, are you going to read this article I sent you—what a toxicologist says about ‘clean beauty’?”

“No, no, no!” they’ll say. “Natural is better!”

And that’s because a lot of these women just don’t have the scientific basics. They don’t have critical thinking skills. And I’m not blaming them—I’m saying it’s very, very hard when you’re up against this shrewd and clever marketing. And that’s why they can’t tell, and that’s why they end up falling for things that have no basis in science.

Sorry, I feel very passionately about the misinformation I see in every top publication—even though I used to contribute to it.

I mean, eight-to-ten articles a week—I know what it’s like to be on the clickbait treadmill.

No wonder I couldn’t talk with experts!

Right? Like, that’s the internet, though. It runs on people cranking out content, and it’s impossible to put out anything of quality at that speed.

It was embarrassing to have to be honest in this book about all the things I did or saw at The Today Show. I worked there for seven years, and that’s like the crème-de-la-crème of morning news shows. But it’s four hours to fill per day. You think anyone was fact-checking the people we put on that show or the people we put on the website? We would publish stuff about studies all the time, but we never read them—we never read them! We’re just feeding these things to people, driving them crazy! One day, red wine’s good for you; the next day, it’s not! We drove women nuts.

And that’s because we needed eyeballs. We had to hit ad fill deals. None of this is based on actually trying to inform the consumer. It’s a game.

You talk a bit in the book about actual scientists, actual doctors, creating social media accounts to try to combat Food Babe and similar people who are spreading misinformation. And I read that, and I’m like, “Well, it’s good that they’re doing that, but it really seems like a little bucket fighting against a tidal wave, or whatever.” Social media especially just seems driven by bullshit. Like, the algorithm just feeds on that stuff, to the point that I’m just convinced social media is toxic by design—which is why I’ve left it and barely even looked back in the last few months. And, I don’t know—do you see a light at the end of the tunnel here? Is there hope for the internet? Or for TV, for that matter?

I spent several weeks on a recent piece for The New York Times about the science-based influencers, and I asked them the same exact question—“Like, it just seems like you guys are going up against an army.”

And I forget what exactly one of them said, but it was something like, “Yeah, there’s one of us for every seventy crazy, non-science-based influencers.” I won’t go into all of it, but this goes into the fact that these people are not supported by institutions, they’re not supported by our government. They don’t make any money off of these efforts, because where would they make money? They don’t have a detox diet or supplements to sell. They burn out so quickly. So yeah, it’s a huge, huge problem.

But there’s also trial and error. I mean, this is separate from the influencer question, but there is just trial and error, right? Like, “I bought this thing, and it didn’t work.” Skin care’s a really great example—people want to know what’s going to get rid of wrinkles, what’s going to make their skin look better, what’s going to get rid of acne. And when they buy a bunch of “natural” crap and it doesn’t work, they’re like, “Yeah, I’m gonna go back to the ‘chemical’ stuff.” So that’s part of it too.

But I do think these influencers are having a little bit of an impact. I don’t know, I quote Food Science Babe, who says, “Every time I feel like I’m making progress, ten more crazy nuts join the fold.” So it is a problem. But I will say that—and this is going to make it into the New York Times piece—there is a concerted effort to these have conversations about “How can the government support these initiatives?” So I think there is hope. I just don’t think we’re there yet.

I really want to talk about the religion angle here. Obviously, you called the book The Gospel of Wellness, so you’re deliberately invoking religion as an analogy. I feel like I’m hearing a lot of things compared to religion these days. I just read Woke Racism by John McWhorter—do you know John WcWhorter?

Am I allowed to say this? I’m a big fan. I know he’s controversial.

Yeah. He wrote this whole book on “wokeness,” or whatever you want to call it, where he says, y’know, “These kids who believe this stuff, they’re just religious zealots, so you can’t argue with them.” Or obviously, I’ve heard countless people compare QAnon, or MAGA in general, to a religion. And I guess what I want to ask is, to what extent is it helpful to compare things to religions? Is there a downside to overusing the comparison?

I don’t know if I could answer that. I’m not a religious sociologist. I did speak at a religious seminary in Jerusalem, and I feel pretty comfortable with religion. I was raised Orthodox Jewish.

But I try to use the analogy with a very light touch. I’m not saying people leave organized religion and then look for a replacement. It’s more about the things we’re missing in American culture.

I do see so many women—and again, I’m at ground-zero for wellness, I’m in Los Angeles—I do see people who are missing community, identity, meaning, purpose. And they get that from the pursuit of health. And I don’t think it helps them, because you can’t win this game. Your body is going to break down. People eventually get sick. There are so many things that you’re genetically predisposed to. And this is where I think it’s really, really dangerous.

Or even light-touch examples, like “Oh, we’re gonna call my gym a church, we’re a tribe”—but you know how many people I spoke to who lost their jobs, and still wanted to go to their gym, and their gym was like, “No dice”?

I don’t think organized religion is perfect, but they’ve had centuries to perfect their craft. If you go to your church, or if you go to your synagogue, and say, “I’ve fallen on hard times—can I still come?” they will generally let you come.

I’ve also spoken to people who got sick, or—oh! I’ll give a great example: “I’m pregnant. I was kicked out of my gym because they’re terrified of having a pregnant person in class. There goes my community.”

You can’t base things on your physical health. Because that’s worshiping your body, and that only gets you so far.

So that’s where I bring in the comparisons to religion, and I say it very tongue-in-cheek, because I see a lot of women, especially white, upper-middle-class women, who don’t feel like they have any way to have a good identity. They feel like they’re just Karens unless they do something special with themselves. And this is one way to get respect, right?

And I’ve seen it—I’ve seen a girl show up with her perfect body, and her little Lululemon sports bra and leggings, and say, “Oh, I just came from a workout,” and everyone’s like, “Oh, bravo! You’re taking care of your health!” I mean, is it that great? Is she so special? I don’t know. That’s the weird thing—we’re just kind of applauding self-absorption.

And people might take aim at that. I’m not saying everyone has to be an intellectual. I’m not saying everyone has to join some social justice movement. But I just worry how far some people are going with this. Now I don’t think the average person is doing that, but for some groups, for a very small sliver, it’s taking on sort of a religious framework. It’s telling them how to live. “I can’t move forward until I know exactly what foods I can eat, how much I can work out!” They’re so dependent on all these influencers and all these magazines to tell them how to live their lives—when it’s pretty simple! I think we all know what to eat! Don’t eat too many processed foods, eat your vegetables. They’re debating the five percent that could be a little bit better, and people just become obsessive about it.

I don’t think it’s helping women. At all. And I think it’s leading to things like orthorexia and fitness OCD. I see wellness apps adding things like streaks and tracking—why do I need to track how much I meditate? Why would I need to do that? This is the type of stuff that people from other countries see, and they’re like, “That’s weird.” But we don’t think it’s weird anymore. We take it as a given. We don’t think it’s weird when we go to Whole Foods and we see detox kits—detox from what? This is what I’m saying. We’re just accepting all this bullshit.

I think I heard Jonathan Haidt—are you familiar with Jonathan Haidt? The moral psychologist?

Ah, now I know that we’re political siblings. You follow Freddie deBoer as well?

…yeah.

All right, all right, now we’re talking.

This is why you liked my podcast, I guess. But yeah, I heard an interview with him—I think it was on The Ezra Klein Show, back in the day, where he said something like, “I disagree with St. Augustine that God exists, but I agree with him that everybody has a God-shaped hole.” Y’know, that there’s this religious need in people, even if there’s not necessarily a God to fill it—and that if you don’t seek out religion, you’ll probably end up filling it with something else.

You’ll worship something. You’ll worship money, success, your body. I think I include that speech from David Foster Wallace, where he talks about that. I mean, I’m not saying people should go join a church, I’m just saying, be cognizant of what you’re falling for and where it can lead you.

And I do think that, regardless what what you think about religion, there is something to be concerned about with the relative death of religion in Western Civilization. Suddenly, there’s no fundamental source of community and values for people. Even if you don’t like the values you get from religion, that seems like a real concern—that suddenly we don’t have anything we agree on, we don’t have an excuse to get together.

And again, I grew up probably not like most Americans, I grew up Orthodox Jewish, but my parents didn’t make plans with friends. They would go to synagogue every weekend, and their friends would just be there. And that’s something that, when I was living in New York City in my twenties and thirties, that felt really lacking. I felt like wanted to see people, but I was tired of making plans. I just wanted a built-in community. And people find that oftentimes with their jobs, and that’s great, but not everyone does. There’s a real loneliness epidemic, and again, I’m not saying organized religion is the answer, but we haven’t come up with a suitable answer for a whole bunch of people.

I don’t know how much of my show you’ve listened to, but I had an episode toward the end where I actually interviewed my own sister. For a lot of years, she was a diagnosed tokophobe—“tokophobia” being the fear of pregnancy and childbirth—but I guess she “got over it,” so to speak, because in January, she gave birth to her first child.

Anyway, she said something to me that really struck me. She said, “I was afraid of childbirth, I was afraid of pregnancy, because I wanted to maintain control over my body, but because I was so obsessed with trying to control my body, I was losing control of my mind.” I was really struck by that—and just by the thought of how illusory control over our bodies is. Like, I feel great these days, because I work out every day, and I’m eating right, finally, but I could be diagnosed with cancer tomorrow, and there’s nothing I could do about it. And I really appreciate what you say in the book about how these religious substitutes like wellness, they can maybe tell us how to live, but they can’t tell us how to die.

And I make the argument that the chief thing that wellness is selling is the mirage of control. “If you eat this thing, if you work out this way, if you meditate this much, then all will be well. You just have to control your body and mind, and everything will be good”—which we all know is not true. And I understand why, because I think American women especially feel like things are out of control.

But the example you gave with your sister is very akin to what orthorexia is, which is you’re so obsessed about eating “clean” and eating non-processed food that you can give yourself an eating disorder, where you’re too obsessed and it ends up controlling you. And this is what happens a lot of times with fad diets—and obviously, I’m not against nutrition, and if you work with a doctor and they need to put you on a specialized diet, that’s fine—but these fad diets, I see people all the time in Los Angeles, and maybe you’ve met them, where people become obsessed like, “My keto diet!” and they can’t go out, or they can’t eat this, and it starts to control their lives, and it’s hard for them to enjoy things. And that’s where it becomes problematic.

And we can’t control our bodies. We can’t control our biology. One thing I didn’t include in the book, but was probably one of the more interesting things I’ve ever covered for Fast Company Magazine was that I attended an “Overcoming Death” conference, which was basically scientists and very, very rich senior citizens who are trying to “cure death.” And that, to me, was where the biohacking movement will ultimately end up. It was people who would not accept that they would get sick and they would die. They could not accept it, they wanted to control it. And it literally felt like the sequel to Get Out—I was like, “Oh my God, I’m under fifty, they’re going to try to get my blood!” And I felt sympathy for them, but they just couldn’t accept that life is uncontrollable.

And I see elements of that within the wellness industry. I’ve had women who told me that they’d break down crying in an aisle at Whole Foods because they’re like, “What here won’t give my kid cancer?”—as if they can control those things. And that’s the problem with this industry—the onus is on the individual. If anything bad happens to you, it’s because you didn’t work out enough, and you didn’t eat right, and you didn’t do x-y-z. It’s victim-blaming. And a lot of these things are just genetic.

And the obsession people have about their beauty creams, or their mascara, or whatever—they don’t even realize that the things that are affecting them more are air pollution and the water they drink. But there’s no money to be made in telling someone not to breathe.

So what’s the lesson here? “As long as there’s money to be made, someone’s going to be spewing bullshit”? Is there any solution, or…?

Yeah, I think I include some thoughts in the last chapter. Follow people who are actual experts in their field. If you’re curious about what sorts of “toxic” ingredients are in beauty products, follow toxicologists, not dermatologists or beauty influencers. If you have someone like Vani Hari, where a very high percentage of the nutrition and dietitian community says she’s full of shit, don’t follow that person. I mean, there are safeguards that we can put around ourselves.

And just realize you can’t control everything. And that’s it.

I have one more thing I’m curious about. You’ve mentioned a couple of times now that you feel like you blew up your career with this book, and you’ve mentioned that this industry is fairly powerful. Has anyone been trying to shut down this project?

Well, I was threatened twice with lawsuits. But it’s more that no one wants to hear these things. There’s some degree of “Well, we don’t know, and let’s keep an open mind.” And the supplement industry’s so big, and the “clean” industry is so big—

I always think about how the tobacco industry managed to suppress all the bad health stuff about tobacco for, like, fifty years before it finally came out. So powerful industries are, y’know, powerful.

Totally. And now that celebrities have become investors and spokesmen for so many natural beverages, natural snack brands, CBD stuff—there’s a lot of money funneled into it. And to some degree I don’t blame magazines—this is how they’re supporting themselves. I would say the wellness industry has basically replaced the beauty and fashion industries, in terms of buying advertising—and magazines are beholden to advertising money. I understand that.

I’m very tongue-in-cheek. I’m not being literal about blowing up my career. I had a piece recently in the L. A. Times, I had a piece recently for the New York Times. I definitely don’t want to say I blew up my career. But I would say I’m persona non grata at women’s magazines. They don’t want to hear this. And also because I take aim at their shoddy reporting—and by the way, I did some shoddy reporting, too. But I own up to it, and I want to do better moving forward, and I do. But they don’t want to admit that.

And you’ll see this all the time. Here’s a great example: I don’t know if you’ve been following the F Factor lawsuit and feud—it’s a very famous influencer diet that’s now in a lawsuit, and dietitians attacked it. And you have all these women’s publications that are like, “Oh, this diet’s so problematic, and the founder’s kind of problematic”—but they’re the same ones who were touting it just three years ago. But they’ll never admit it. And I wish they were more honest, like “Hey, we screwed up.” But that’s not how this works.

Thanks again to Rina for giving me her time. I wasn’t compensated for this interview in any way, unless you count the free book, which, y’know, free books are cool (keep scrolling to get a couple from me). Here’s yet another link to where you can buy The Gospel of Wellness. I guarantee it’s printed on gluten-free, fair-trade, organic paper that was blessed with the power of crystals (maybe).

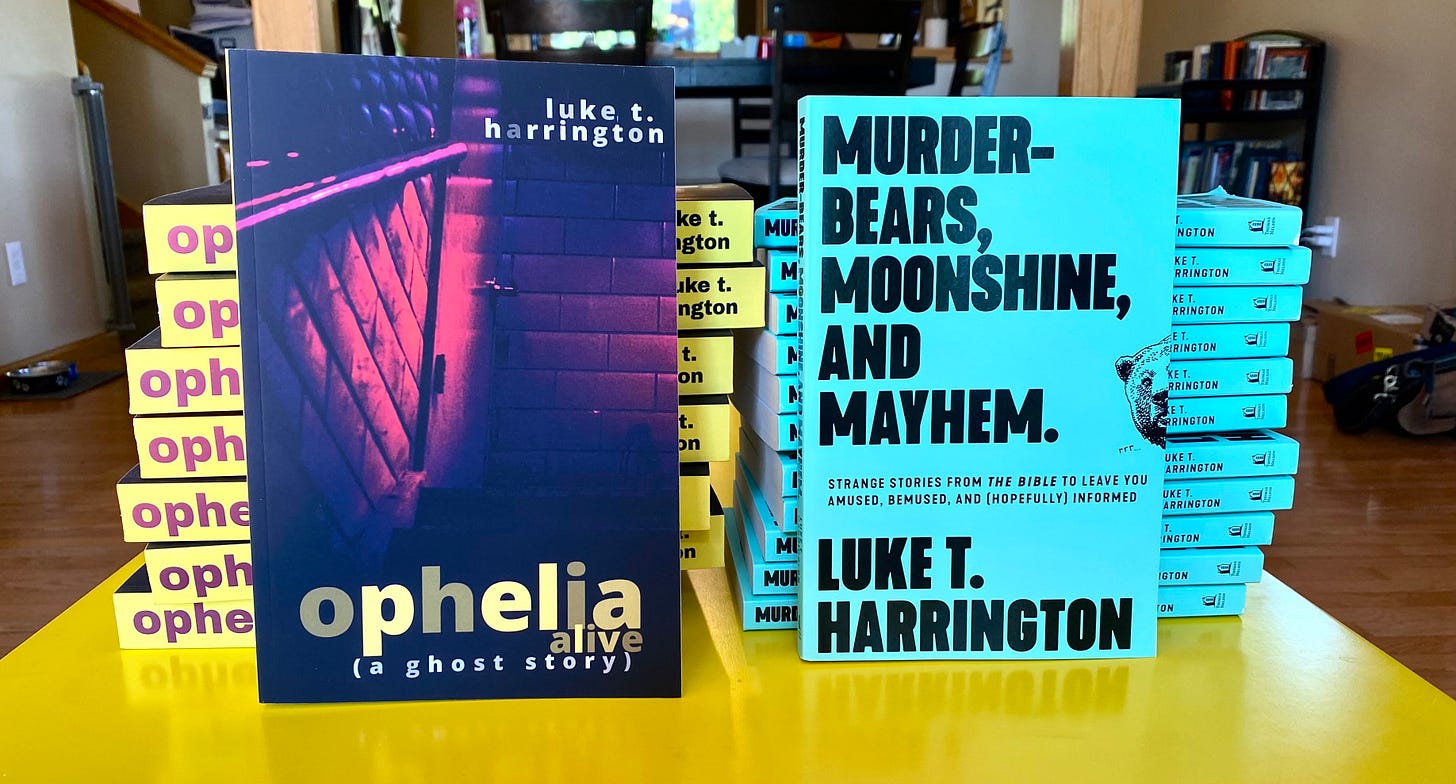

It’s a veritable cornucopia of free books

Hi to any new readers! I’m a horror author and occasional humorist out in Madison, Wisconsin, and these days, I’m working on building my audience here on Substack. So here’s how this works:

Everyone who signs up to receive this newsletter in their email inbox immediately gets free ebook copies of both my published books.

Every month, I hold a drawing for signed paperback copies of each book as well. (Everyone who signed up the previous month is eligible.)

“And just what books are those, Luke???”

Well:

Ophelia, Alive: A Ghost Story, my debut novel about ghosts, zombies, Hamlet, and higher-ed angst. Won a few minor awards, might be good.

Murder-Bears, Moonshine, and Mayhem: Strange Stories from the Bible to Leave You Amused, Bemused, and (Hopefully) Informed, an irreverent tour of the weirdest bits of the Christian and Jewish Scriptures. Also won a few minor awards, also might be good.

So you’ll get both of those, plus my monthly thoughts on horror fiction, musicals, and why social media is bad and you should feel bad for using it. Just by entering your email address below:

Congrats to last month’s drawing winners, email addresses beginning with swagg003 and jill.r.carvalho. If you are one of those people, please reach out to me! I’ve been trying to contact you to send you your signed books (and also to talk to you about your cars’ extended warranties), but I’ve gotten no response, and I’m starting to feel like a stalker.

Stuff I’ve been enjoying lately

A week or three ago, I watched the Netflix docuseries Trainwreck: Woodstock 99. It’s entertaining enough, if you don’t mind feeling a desperate and irrational need for a shower. Like any decent doc about Woodstock’s thirtieth anniversary spectacular would, it attempts to answer the question of how an ostensible celebration of peace and love managed to collapse into deadly riots—and the best answer seems to be that the event just oozed cynicism (and also just literally oozed various unpleasant fluids). Event organizers treated their customers with contempt from the moment they walked in the gate, and the customers were more than happy to return the favor.

Chuck Klosterman’s recent The Nineties: A Book is a somewhat more serious analysis of the unique sort of universal cynicism that characterized the decade-long Pax Americana between the end of the Cold War and the dawn of the War on Terror, and I enjoyed it quite a bit more than I expected to. The nostalgia-flavored cover made me roll my eyes a bit, and Klosterman’s reputation as the hipster author the Cool Kids like made me put off reading him for years, but when I finally got around to reading The Nineties, I was pleasantly surprised by how insightful and breezily written it was.

I couldn’t even put it down at my nine-year-old daughter’s inaugural cross-country meet, which I’m sure annoyed my wife to no end. Sorry, daughter (and wife)—I’m proud of you for running a mile, but I was too busy finding out why no one associates Garth Brooks with the nineties, even though he sold more than twice as many albums as Nirvana (the answer, of course, is “zeitgeist”).

The Nineties is well worth a read. Trainwreck, meanwhile, is…well, it delivers on the title for sure.

This whole post felt like a balm to the soul. Wait…..

Luke & Rina’s Soul Balm: clean, natural, non-toxic. Renews lost serenity. Cleanses bullshit.

She sounds like a lovely person