***The following review contains minor spoilers for Sarah Rose Etter’s Ripe: A Novel.***

Back in September, The Free Press and the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression (FIRE) organized a public debate that received a fair amount of attention, at least on the corners of the internet I frequent these days. Daily Mail journalist Louise Perry and Red Scare podcaster Anna Khachiyan (on the “no” side) and ex-Muslim activist Sarah Haider and pop singer Grimes (on the “yes” side) went back and forth on the question, “The Sexual Revolution promised liberation. Fifty years on we ask: Has it delivered?”

I haven’t watched the debate, but I do find myself repeatedly coming back to this reflection on it by author

. Henderson’s argument, paraphrased slightly, is something like, “Duh, obviously the Sexual Revolution led to liberation (in the bare sense of increased freedom); the only reason we’re having this debate at all is because it failed to increase happiness.” Because our culture (to paraphrase Henderson further) thinks of both freedom and happiness as unalloyed goods, we tend to imagine they go hand-in-hand—but of course freedom and happiness are often mutually opposed: Who among us hasn’t sat down, planning to find something to watch on Netflix, only to become overwhelmed at the nearly infinite choices, and just given up, more stressed than when we started?The debate was (obviously?) centered around the female perspective, so if you wanted to, you could probably accuse Henderson, as a man, of being presumptuous in opining at all about what makes women happy—but Henderson’s argument is fundamentally data-based, and it’s not exclusively about women, anyway: self-reported happiness has declined precipitously for both sexes in the post-Revolution era—but significantly more so for women than for men. As Henderson puts it, “…our grandmothers were happier than our grandfathers. Over the past several decades, though, this has reversed. Men are now happier than women.” (Moment of silence for those who just now learned that their grandparents had sex.)

Henderson goes on to cite statistics showing that only eleven percent of women report experiencing orgasm in casual hookups, versus sixty-seven percent in committed relationships, but even setting the data aside, there’s a pretty clear reason why women would find casual sex less satisfying than men do: they’re the ones who tend to get stuck with the proverbial bill. Aside from the obvious risk of unwanted pregnancy, straight women are just far more likely to be harmed or even killed by their sexual partners. Women assume most of the risk of casual hookups; men get most of the pleasure—that’s just an unavoidable consequence of physical reality.

And all that is just one illustration of how freedom for all has a way of devolving into freedom for only the most powerful (“Freedom for the pike is death for the minnow,” as Perry put it in the debate). If you express that reality in economic terms (“Capitalism inevitably leads to oligarchy and wage slavery!”), a left-leaning crowd will cheer; if you point out that it’s true of sex as well (“Sexual freedom mainly benefits powerful men, and it’s not for nothing that ‘manufacturing consent’ is a catchphrase”), that same crowd will respond with considerably less enthusiasm.

Last summer, though, I read a novel that connects those dots—though how intentionally it does so, I can’t say—and it’s haunted me ever since. More on that after the break:

Hey there, stranger! Welcome to my newsletter. If you sign up to receive it in your email inbox, I’ll send you e-copies of both my published books for free, and enter you in a drawing to win a signed paperback copy of each. You can scroll to the bottom of this post for more info, or else just enter your email address here:

***

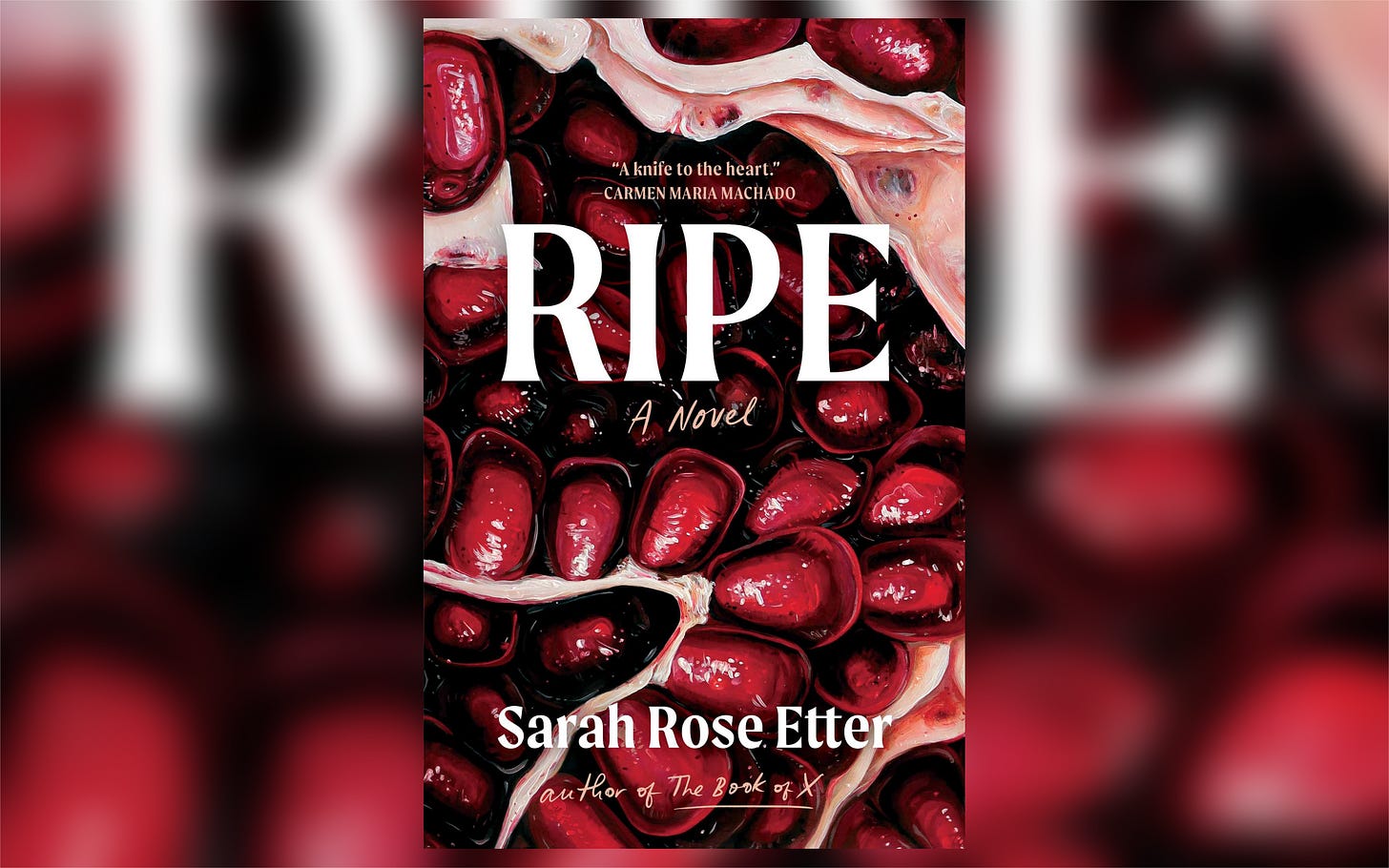

This is the part of the essay where it turns into a review of

’s Ripe: A Novel, so I may as well lay my cards on the table here and tell you what I thought of the book: I was super annoyed by how good it was. Super annoyed—because, when you list them out, the book’s basic components sound extremely Freshman Fiction Writing 101: Ripe’s protagonist, Cassie, has been followed around since birth by a miniature black hole (it’s a metaphor for depression, you see). Her upbringing was Midwestern, Catholic, and (surprise!) traumatic. Despite her prestigious tech sector job, she’s still miserable and addicted to coke. She’s surrounded by phonies and relies on what she calls her “fake self” to get through all her day-to-day interactions.In other words, Cassie is an older, female, drug-addled version of Holden Caulfield—and she’s a lot worse off than he is, because she’s bought into the phony economic power machine they both hate. She’s also dealing with a problem Holden never had to deal with: an unwanted pregnancy, resulting from her frequent hookups with a man in an “open relationship.” In short: Cassie has managed to get herself thoroughly tangled in the invisible, omnipresent web woven from economic and sexual freedom.

The comparison to The Catcher in the Rye is, I think, an apt one, since both Catcher and Ripe are novels that succeed despite their insufferable protagonists. Part of that is that J. D. Salinger and Sarah Rose Etter are both master prose-smiths, but part of it, too, is that their respective main characters’ complaints against the late-capitalist world are apt: the world we exist in is, in fact, loaded down with mountains upon mountains of stupid bullshit, and one needn’t propose a solution to said bullshit in order to correctly observe it.

The bullshit in question is all evident in Cassie’s day-to-day life in San Francisco: Much of the text of Ripe is devoted to discomfiting juxtapositions of the excesses of the IT industry and the squalor of the city’s notorious homelessness problem. Cassie starts every day walking to the station and riding the train to work, striving the whole time to avoid making eye contact with the people doing drugs and defecating in public—people who, no doubt, would react less than appreciatively if you tried to lecture them about the glories of the free market.

Cassie is, of course, materially better off than these poor souls, but no less trapped by economic realities. She’s done everything “right”—“learned to code,” as they say, and landed a six-figure job with one of those tech upstarts we’re all supposed to be excited about (not that six figures is much in the Bay Area, but you get the point)—yet none of it has made the black hole go away, and in fact, said black hole only gets larger as her employer keeps demanding that she lie to potential recruits and do literal crimes to undermine competitors. And, sure, she’s “free” to seek alternative employment—if she can find a way to pay her sky-high San Francisco rent while she’s looking.

Her love life is in the same general space: She spends occasional afternoons with a professional chef who brings her custom donuts and joins her for Netflix-and-chill. But he’s already got a committed relationship and makes it clear that he doesn’t—can’t—love her (“I can only like you very much”). When the birth control fails and she finds herself pregnant with his child, she discovers she’s incapable of even telling him. How could she, when he’s made it clear he’s only with her for the lulz?

*(Minor spoilers follow.)*

Cassie occasionally indulges in daydreams of marrying her chef and raising her still-embryonic child, but ultimately the pregnancy ends the only way it ever could have: at an abortion clinic. It’s this climactic abortion that elevates Ripe as literature and ties it together thematically, functioning as the inevitable result of endless economic and sexual freedom. Like everything else, abortion is a “choice”—one nearly always chosen by those who have no other choice. Cassie could have “chosen” instead to birth and raise her baby, but only if she could have found a job with a living wage and schedule flexibility, or a father willing to stick around and help out—but neither of those things was on the market. The freedom wielded by the powerful had already made those choices for her.

*(End spoilers.)*

***

By random happenstance (i.e., my chaotic reading habits), I read Ripe sandwiched in between The Catcher in the Rye and Jay McInerney’s 1984 novel Bright Lights, Big City, and the three books all struck me as weirdly of-a-piece. What does it mean, I found myself wondering, that the twentieth century birthed an entire genre of novel best described as “mostly plotless thing where the main character spends 300 pages wandering around a major metropolitan area feeling miserable”? Aside from the obvious answer (“Duh, it’s James Joyce’s fault”), I suspect it might be the inevitable result of a culture with values that often find themselves directly at odds with one another—i.e., freedom and happiness.

A fourth book I read around the same time, psychologist Batja Mesquita’s Between Us: How Cultures Create Emotions, helped clarify some of these thoughts for me. According to Mesquita, there really are no universal “primary colors” of emotion: Cultures define and distinguish emotions in infinitely many ways, and plenty of languages don’t even have words for emotions most Americans consider elementary. Among the languages with words for happiness (which is far from all of them!), many would define the word differently from how Americans do (for example, as something more akin to calmness or contentment)—and some don’t even consider it to be a pleasant or desirable feeling.

No doubt a lot of Americans would be bewildered by that revelation—what could be more desirable than happiness?—which of course shows you how deeply unaware most of us are of the assumptions we’ve spent our lives swimming in. But is it possible that chasing after happiness is a fool’s errand?

Ours is a culture that pushes new adults out the door into a world of endless freedom and tells them, “Okay go find happiness!” But given how overwhelming and constraining freedom can be, and how elusive and fleeting happiness is, this sort of approach is setting up a whole lot of people for failure—especially when you take into account that many of us are just born with our own personal black holes.

***

It’s tempting to dismiss Ripe as yet another disillusioned MFA telling the whole world to get bent, but I can’t bring myself to do it; this book has consumed my thoughts over the months since I’ve read it, and I’ve struggled to put my finger on exactly why. Part of it, no doubt, is Etter’s spare, evocative prose, which effortlessly turns ugly things beautiful and beautiful things ugly; there’s more to it than that, though, and I suspect it lies in one of Cassie’s simpler habits.

While Cassie’s reflections on her childhood often drip with the same contempt she pours out for Silicon Valley, she never finds herself truly able to say goodbye to it, and in fact calls her father almost compulsively. He’s semi-retired now, but spends most of his time working in a grocery store, trying to cover some of the debts racked up by Cassie’s abusive spendthrift of a mother. He consistently encourages her to stay in the tech job, telling her “There’s nothing here for you,” but I wonder how true that is. Cassie’s dad embodies something we see in almost no other character in Ripe: a willingness to live his life for the sake of others, even when the others in question clearly don’t deserve it. No doubt Cassie wonders why she can’t find someone in the Bay Area like her dad—or possibly why she can’t be someone like her dad.

This handful of phone conversations makes for the one bright spot in what’s otherwise an oppressively bleak read—and for my money, one of the most clear-eyed looks at the empty world we’ve built for ourselves. Ripe offers no solutions, but I find that refreshing as well; there is, after all, a time to mourn. Sometimes, you just have to sit and gaze into your own personal black hole. 🕹🌙🧸

I’m almost positive that free books lead to happiness, though

Hey, thanks for reading! If you’re new to this newsletter, here’s how it works: everyone who signs up to receive it in their email inbox gets free e-book copies of both my published books, plus you get entered in a monthly drawing for a free signed paperback copy of each! Why? Because I like you.

So, just for signing up, you’ll get:

Ophelia, Alive: A Ghost Story, my debut novel about ghosts, zombies, Hamlet, and higher-ed angst. Won a few minor awards, might be good.

Murder-Bears, Moonshine, and Mayhem: Strange Stories from the Bible to Leave You Amused, Bemused, and (Hopefully) Informed, an irreverent tour of the weirdest bits of the Christian and Jewish Scriptures. Also won a few minor awards, also might be good.

…plus my monthly thoughts on horror, the publishing industry, and why social media is just the worst. Just enter your email address below, and you’ll receive a monthly reminder that I still exist:

Congrats to last month’s drawing winners, a.surbatovich and ellegebhardt! I’ll run the next drawing Mar. 1! 🕹🌙🧸

You think 1950s housewives had orgasms?